One such was Major-General Sir Frederick Barton Maurice, a British officer who served in the Tirah Campaign, the Second Boer War, the Battle of Mons and the First World War, and later became a military academic and correspondent. Maurice was a military man, but he believed that if Europe was to avoid another war limits must be set on arms. Not long after the war ended, in the early 1920s, he wrote about disarmament for journals such as The Contemporary Review. He outlined why disarmament should take place, an interesting argument to hear from a Major-General.

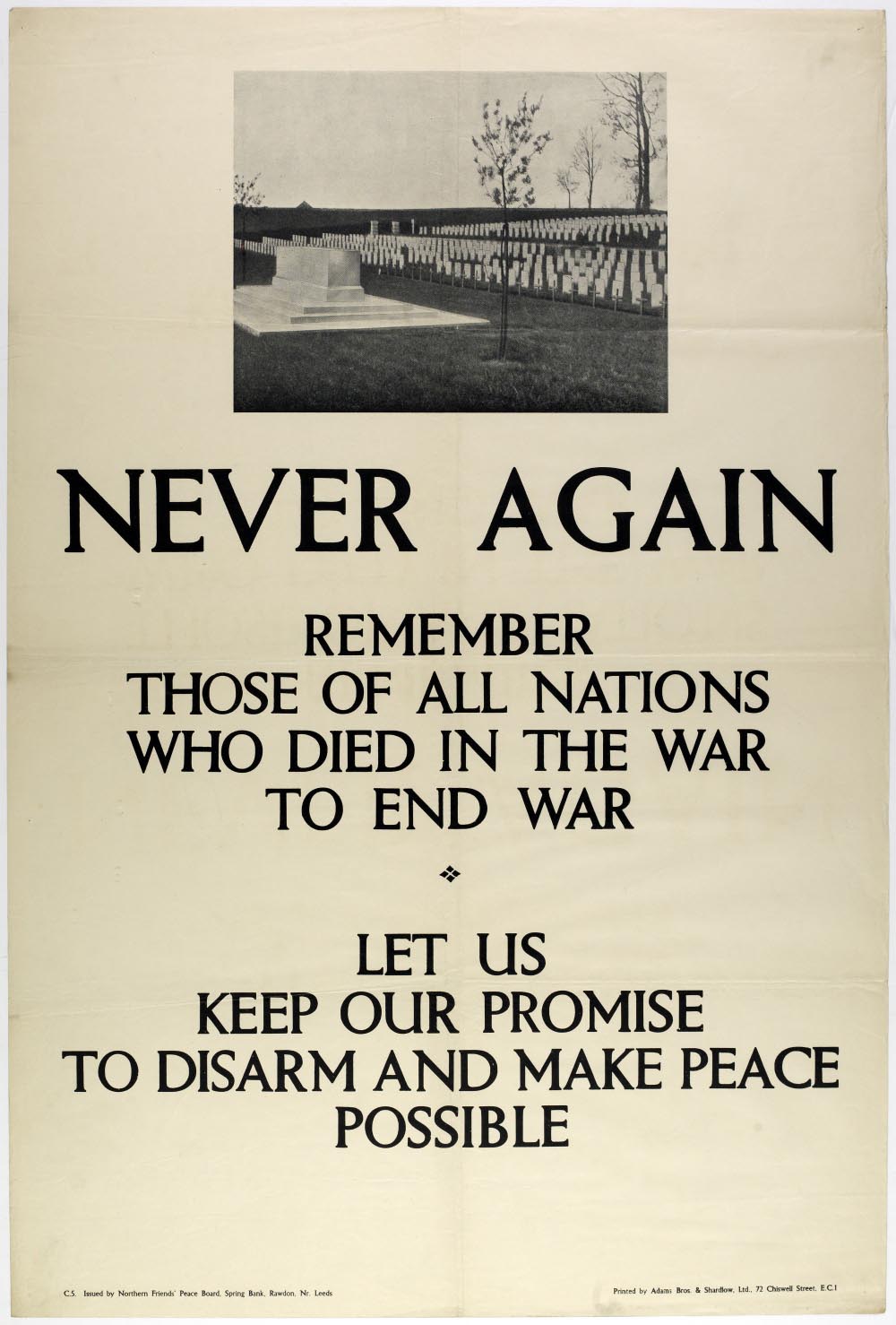

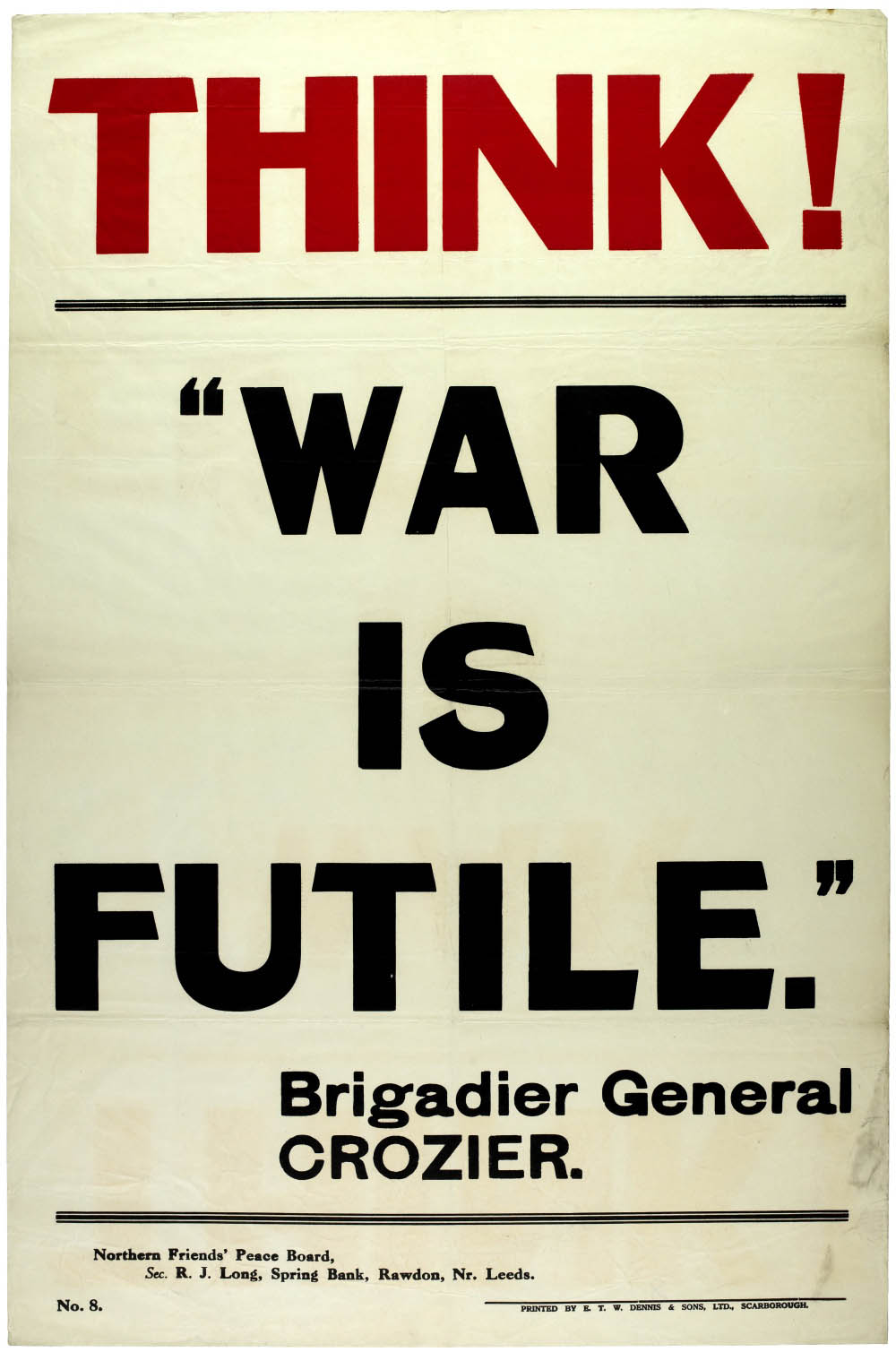

A poster using a quote by Brigadier Crozier who joined the Peace Pledge Union/© Northern Peace Union

A poster using a quote by Brigadier Crozier who joined the Peace Pledge Union/© Northern Peace UnionIn The Limitation of Armaments, published in 1921, Maurice discusses how public opinion had changed since the war: ‘Every anti-waste candidate at recent by-elections has demanded a reduction of expenditures upon armaments in one form or another and the voters have shown their sympathy with the demand.’

He warned that disarmament must be carefully thought out in order to ‘stand the test of time.’ Otherwise ‘we shall sooner or later return to the old conditions, for all past experience has shown that, if demands for the reduction of armaments are accepted on no definite principle, they are invariably followed sooner or later by demands, again made in panic, for increased expenditure in armaments.’

He argued that public outcry against arms was not enough. It was ‘necessary to examine the causes which brought about the increase in armaments, created a nation in arms, and turned Europe into an armed camp.’

Europe and the United Kingdom were financially ruined after the war, partly because of their huge expenditure on armaments. Many, like Maurice, considered the demand for public services to be more important than the need to keep producing extreme amounts of expensive armaments. This was not a new opinion, as debates from before the war show.

In strong terms Maurice argues for money to be spent on social reform over armaments:

‘That the burden is crushing needs little demonstrating. We are today financially in a better position than most of the nations of Europe, yet we are in grave doubts how the Budget for next year is to be balanced; social reforms which involve expenditure are at a standstill; we are making drastic cuts in the supplies for education and for housing; our hospitals are seriously embarrassed; our industries are crippled; our unemployed number more than 1,500,000, and yet in the last financial year we spent more than £23 million upon armaments. No wonder the taxpayer grumbles and the financiers shake their heads.’

Above all, Maurice worried about how to stop another war from happening. He suggested that it was a mistake to impose a reduction of military strength on the defeated powers alone; the victors should also have taken the opportunity to disarm alongside them.

Instead, the only progress that had been made was an agreed reduction of expenditure on naval power.

Like many at the time, he believed that a solution could be found in the League of Nations: ‘Preparation for war, carried to its possible limits, is a prime cause of war. If the reduction of armaments is to be permanent, if another war more terrible than the last is to be avoided, there must be other forces at work than a demand for economy. A new principle must be applied; and no one has yet discovered a better principle than that of the League of Nations, which proposes to substitute for the spirit of competition between nations the spirit of co-operation and concentration of force for a balance of force.’

Military spending now comprises six percent of government expenditure. This is a much lower proportion than before the First World War because of increases in other government spending such as health, education, and welfare. The UK still has the sixth highest military spending globally and the Ministry of Defence has faced much smaller cuts than many government departments since 2010.

When the UK Government claims that there is not enough money to continue to pay for public services such as health, welfare, and education, it is worth considering the military expenditure that they are willing to pay for. The government has little problem paying for such things as fighter jets, aircraft carriers and nuclear weapons.

Alternatives to military spending

The government spends 30 times more on weapons research than tackling climate change. Because arms jobs are paid for by taxpayers, resources can be redirected, and by shifting their priorities from defence spending to combatting climate change, the government could have a dramatic impact. They could secure green jobs for the future and improve, rather than threaten, human security.

Every year £700 million of public money is spent supporting arms exports, often to countries in conflict and regimes that abuse human rights. This subsidy is handed to an industry that accounts for fewer than 55,000 jobs.