At the outbreak of the First World War Britain’s industries were unprepared to produce the enormous amount of war material that would be needed over the next four years. Although production increased 19 fold in the first six months of the war it still wasn’t enough. By June 1915 there were shortages of munitions, including a 97 percent shortfall of explosive shells.1

This became a major scandal in the press, whipped up by the press baron Northcliffe. When the war began the supply of munitions had become the responsibility of the Armaments Output Department, part of the War Office.2 In August 1914 the state-owned ordnance factories were providing the Army with about a third of its weapons and there were just 16 firms tendering for War Office munitions contracts. 3 Existing machinery to produce rifles, machine-guns and heavy artillery was inadequate. Part of the problem was that the War Office only procured munitions only from established firms, who competed with each other, promising to deliver more than they could produce.

In response, the Ministry of Munitions was created in June 1915 to organize the supply of munitions and to control the supply of materials deemed crucial for war production. 4 David Lloyd George, who had previously opposed war profiteering and the Boer war, moved from his post as Chancellor of the Exchequer to become Minister of Munitions.5 At the end of the war, the Ministry was employing a staff of sixty five thousand (by some estimates) and had over three million workers under its control. They succeeded in increasing production; for instance only 1,330 machine guns were made at the beginning of the war while 240,506 were eventually produced during the war6

- D Stevenson, 1914-1918: The History of the First World War (London: Penguin, 2012), 232. ↩

- F.H. Hatch, The Iron and Steel Industry of the United Kingdom under War Conditions: A record of the work of the Iron and Steel Production Department of the Ministry of Munitions. London: Harrison & Sons Ltd., 1919. Available at ftp.iza.org/dp8129.pdf ↩

- Post by Paul Francis at http://www.airfieldinformationexchange.org/community/showthread.php?11695-FIRST-WORLD-WAR-Ministry-of-Munitions-and-Munitions-Factories ↩

- S.N. Broadberry and W.P. Howlett, ‘Lessons to be Learned: British mobilization for the two world wars’, Draft Paper presented at a conference held at Warwick University 31 March-1 April, 2014 on the Economic History of Coercion and State Formation. ↩

- David Lloyd George, Wikipedia, accessed on 1 May 2014 at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Lloyd_George ↩

- AJP Taylor, English History, 1914-1945, The Oxford History of England (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 23 ↩

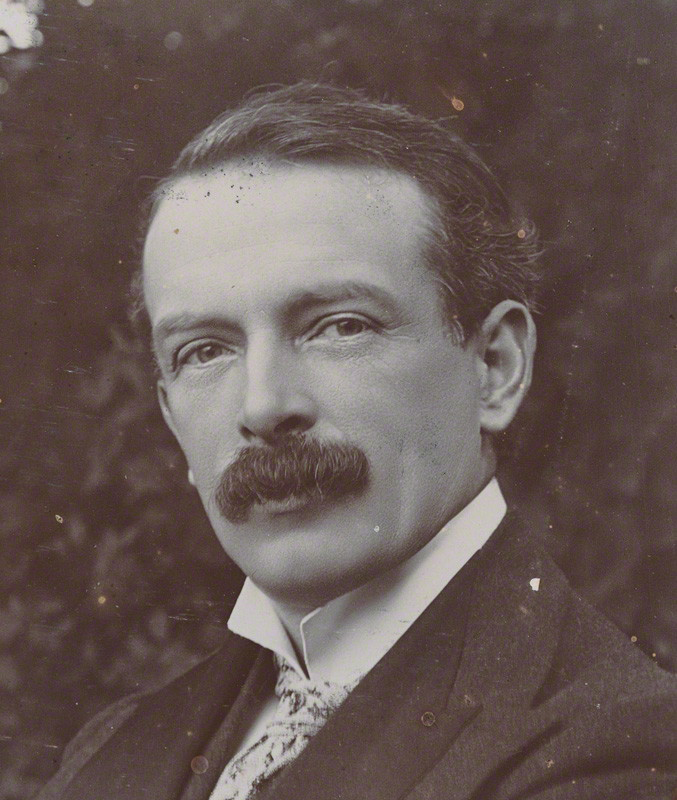

David Lloyd George /© National Portrait Gallery. Creative Commons Licence. http://tinyurl.com/39k5wm

David Lloyd George /© National Portrait Gallery. Creative Commons Licence. http://tinyurl.com/39k5wmThe Ministry assumed control of factories engaged in war production and ruled over such things as work discipline, time keeping, levels of output and profits. The Ministry of Munitions Act (1915) prohibited strikes and lock-outs and introduced compulsory arbitration. By 1916 there were over 5,000 controlled establishments across the country. 1

Nearly one hundred categories of materials were brought under the control of the Ministry of Munitions, not only iron and steel, but also less obvious necessities such as plaster slabs, gas masks, and boxes.2 Ultimately, the Ministry assumed responsibility for all necessary supplies, controlling the distribution of raw material to non-munition as well as munition trades, and thereby bringing all industries involved both directly and indirectly in the production of munitions under its control.

Following the establishment of the Ministry of Munitions new national munitions factories started to be created across the country. The Defense of the Realm Act (DORA), as amended in March 1915, enabled the government to requisition land or to take over and use any factory or workshop. At the end of December 1915, there were 73 new sites and by the end of the war there were over 218 new or adapted factories in operation covering a wide range of munitions and other products used in the manufacture of munitions. These included National Shell Factories (for light shells) and National Projectile Factories (for heavy shells), HM Explosives Factories, Chemical Warfare Factories and National Filling Factories. To run the shell factories, local Munitions committees were set up across the country representing the smaller engineering firms, many of which had acted as sub-contractors to the armament companies. They set up the National Shell Factories using existing buildings such as railway workshops, textile mills and tramway depots. In Swansea, for example, a National Shell Factory was set up in an existing engineering works.

David Lloyd George described the Ministry as ‘from first to last a business-man’s organisation’AJP Taylor

It is surprising, and perhaps indicative of the degree of panic at the time, that recruitment of staff was relatively uncontrolled. A detailed interim report on the organization and structure of the Ministry written by two senior civil servants in early 1916 shows there were few, if any, proper procedures in terms of deciding which jobs were needed, how many of them were needed and how they should be filled. 3

The Ministry was staffed by a mixture of:

- A number of established civil servants seconded from other departments

- Senior (and sometimes not so senior) people from the armed forces who were either too old or injured to fight

- People from the business community, some of whom were recruited as volunteers (entirely unpaid), some of whom were given subsistence allowances, and some of whom were salaried.

This combination of different backgrounds, cultures and remuneration structures amongst the Ministry’s staff led to compartmentalization, bad communication, duplication and lack of control over costs.

The staff records held for the Ministry in the National Archives contain many different lists of employees and statistical reports which contradict each other. The sources show that there was inexorable growth over the course of the war, but the numbers of people employed by the Ministry remains uncertain. 4

- Taylor, English History, 1914 to 1945, p65 ↩

- SN Broadberry and W.P. Howlett ↩

- Ministry of Munitions, Preliminary Report on Staffing of the Ministry of Munitions February 29 1916 MUN 5242612, National Archives ↩

- Ministry of Munitions, Records at the National Archives Relating to Staff at the Ministry of Munitions, no date, MUN 527263, National Archives ↩

Businessmen at Work in the Ministry:

Sir Édouard Percy Cranwill Girouard, KCMG, DSO was Canadian. Girouard worked on railways across the British Empire, and joined the British imperial ‘Dongala expedition’ to build a railway across the Nubian Desert under the command of Lord Kitchener (who thought highly of him and would later help him be put in charge of Munitions Supply.)

In 1912 he became managing director of the Elswick Works in Tyneside at Armstrong Whitworth, a major arms developer before and during the First World War. From the outbreak of war, he criticized any plans to extend munitions supply to non-specialist companies. He wrote to Kitchener in 1914: ‘It is not to our interest as munitions manufacturers to extend the scope of work nor is it ordinarily practicable to get good work from Companies who know little about the productions of munitions’. In 1915 he wrote, again to Kitchener: ‘these geese who can lay the golden eggs, the armament companies, are … being slowly reduced to impotence’. 1

Girouard only worked at the Ministry of Munitions for a few weeks before being summarily dismissed by Lloyd George. He explained this by saying that he could not bear to work under the direction of politicians. However, elsewhere it was suggested that ‘from the outset his political chiefs were unimpressed with his personality, finding him too ‘anxious to get things into his own hands and … more concerned with his title and functions than with the business in hand’. 2

He may not have lasted long in the job, but he returned immediately to his position at Armstrong. Girouard’s short time at the Ministry certainly raises questions about conflicts of interest amongst Ministry staff recruited from the private sector. For instance, he was keen to get people he knew jobs in the Ministry for ‘princely salaries’. One such was Glynn Hamilton West, another Armstrong employee, who unlike Girouard remained at the Ministry until January 1918.

Sir W. Charles Wright

Statesmen of the First World War by Sir James Guthrie /© National Portrait Gallery. Creative Commons Licence. http://tinyurl.com/39k5wm

Statesmen of the First World War by Sir James Guthrie /© National Portrait Gallery. Creative Commons Licence. http://tinyurl.com/39k5wmSir W. Charles Wright was the son of John Roper Wright who was a partner in Wright, Butler & Co, a Midlands based firm of steel makers. The company acquired (together with Baldwins Ltd. and the Gloucester Railway Carriage & Wagon Co Ltd.) a steelworks in Port Talbot. W. Charles Wright was appointed manager of the Port Talbot works and became a mover and shaker in the South Wales steel industry.

He was brought into the Ministry of Munitions, possibly by Lloyd George himself, to supervise the supply and distribution of steel in June 1915 and remained in that position until February 1916. Along with two other people also associated with the steel industry (Sir Leonard Llewellyn and W. T. MacLellan) he was responsible, among other things, for fixing the price of sheet steel.

Christopher Addison, Lloyd George’s Parliamentary Secretary and Deputy at the Ministry reveals in his diary that he had to remind Wright ‘that he must try to forget that he is a businessman looking after his own interests’. He goes on: ‘Wright had hardly been playing the game by us and has apparently been coaching up the steel makers to demand high terms in connection with the taxation of profits, so as to induce us to allow large reductions in connection with the putting up of extensions in connection with other work… He had apparently been egging on the steel makers to demand at least an allowance of 75 percent on the cost of these extensions and one of them who has some notion of playing the game, has sent us his correspondence’. 1

Despite this clear evidence of price manipulation and conflict of interest, after a period of absence from the Ministry Wright was rehired in January 1917 as a deputy director. As such he was virtually the South Wales agent for steel control. Later the same year he became Controller of Iron and Steel Production and chairman of the Committee on Home Iron Ore Supply.

Baldwin’s, who had been a part owner in the Port Talbot site took over full control of it in 1915 and was able to expand the works (both in terms of size and technology) with financial assistance from the Ministry. In November 1917 the Herald of Wales reported that Baldwin’s profits were amply enough to pay a second dividend that year to shareholders plus a tax free bonus. 2 Whether these short term profits would continue after the war, when the economic situation was less favourable remained to be seen, but what is certain is that companies such as Baldwin’s were able to improve their plant during the war, with the bill being paid by the public purse.

- As quoted in W Charles Wright biography in the Dictionary of Business Biography, quote taken from Chris Wrigley The Ministry of Munitions An Innovative Department in Kathleen Burk (ed), War and the State, George Allen & Unwin, 1982 ↩

- Cymru 1914 – Saturday 3rd of November, 1917, accessed May 26, 2014, www.cymru1914.org/en/view/newspaper/4115748/5/ART155 ↩

Aircraft Carriers

Today taxpayers are picking up the bill for an aircraft carrier project for which the costs have almost doubled, while few are sure what the intended purpose of the carriers is. 1

As at the time of the First World War, arms companies continue to capitalise on their close relationship with government. BAE Systems is the largest corporate recipient of public funds and its contracts to produce two new aircraft carriers is the most glaring example of a military equipment project for which the government has had uncertain aims, but seemingly unlimited funds. 2

In 2007, faced with the decision of whether to purchase aircraft carriers for the armed forces, then Prime Minister Gordon Brown gave the go-ahead for two. Much of the construction has taken place at Rosyth, which borders Gordon Brown’s constituency.

The cost of the aircraft carriers when the government confirmed its main investment in 2007 was £3.65 billion. It is now £6.24 billion after delays, cost over-runs, and u-turns on which aircraft the carriers would carry. 3 Taxpayers picked up 90 percent of these overruns until 2013, and 50 percent since. 4

This has been criticised as a waste of public money, with no clear plan for their use and satirised by ‘Bird and Fortune’ in 2008.

- More at www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-18237029 ↩

- www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2011/mar/02/data-store-government-data ↩

- Page 4 of NAO report into aircraft carriers www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/10121092.pdf ↩

- www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201314/cmhansrd/cm131106/debtext/131106-0001.htm#13110656000003 ↩