Irony is clearly something that came easily to the nineteenth century chemist and industrialist Alfred Nobel who invented ‘superior blasting powder’ along with a safety fuse and detonator. He gave his name to the Nobel Dynamite Trust. The wartime history of this conglomerate shows that politicians were willing to avoid the letter of ‘Trading with the Enemy’ legislation and grant permissions and licences when it came to exchanges of wealth and influence.

The Nobel Dynamite Trust was created in 1886 in order to overcome fierce competition between dealers in dynamite, encouraged by Alfred Nobel who was a shareholder and adviser to fifteen companies. It was one of the world’s first multinational business ventures: a holding company comprised of three British and four German explosives companies. The largest, Nobel’s Explosives Company Ltd, with a head office at Nobel House, 195 West George Street, Glasgow, became a contractor to the British Government in 1907. The Trust loaned these companies capital to advance their businesses and distributed a percentage of the profits that such investments made back to the shareholders of the Trust.

The British and German companies sold explosives all over the world. This arrangement ensured that German shareholders profited from the death of German soldiers and British shareholders profited from the death of British troops for the first two years of the war, especially as share prices and dividends rose during the entire conflict.

The Board of Directors, with 14 members in all, had five individuals representing British companies and four representing German businesses. The remaining five were shareholders. The Trading with the Enemy Act of September 1914 caused some problems for the Trust. This piece of legislation, passed through the British Parliament, made it illegal for any citizen of the Empire to conduct business with anyone of an ‘enemy character.’ However, this law, although clear in its aims, did not cause as much trouble for the Trust as one might suppose.

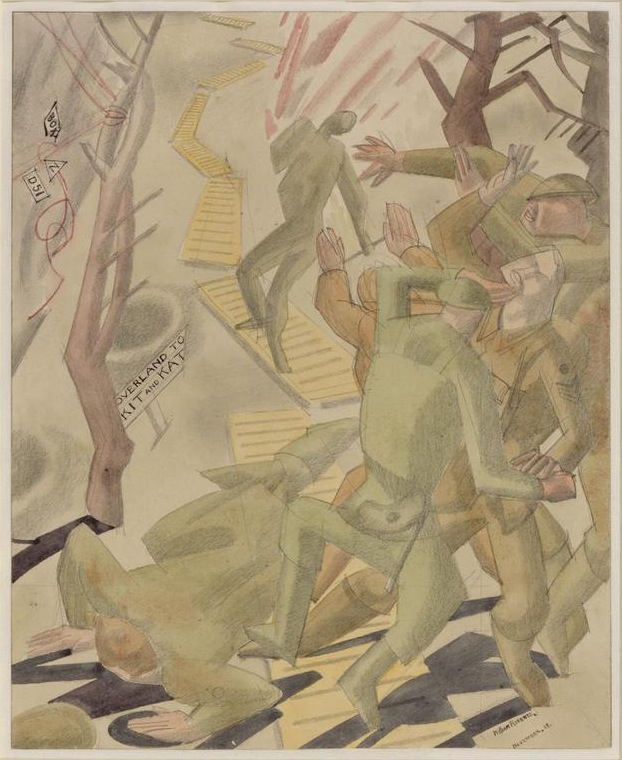

Drawing by William Roberts of a group of British soldiers caught in an explosion as they make their way along a duckboard/© IWM (Art.IWM ART 1170)

Drawing by William Roberts of a group of British soldiers caught in an explosion as they make their way along a duckboard/© IWM (Art.IWM ART 1170)The separation of the British and German interests within the Trust took a long time to actually come about. Although the German members of the board resigned from the Trust in September 1914 (creating one British and one German trust) financial wrangling about exchanging shares and final settlements prolonged the company’s activity for another 22 months.

A memorandum written by British representatives of the Trust to the Secretary of State on 13th May 1915 shows the Government was aware that British shareholders were profiting from British deaths. The Trust’s correspondent realised that ‘patriotic’ business men benefitting from the slaughter of their countrymen could become a public relations disaster. ‘Good businessmen are doubtless much alarmed as to what might be said if the public realised that this was the state of affairs,’ he continued.

The process of winding up the Trust’s affairs was headed by the Undersecretary of State for the Home Office and was mediated by Dutch, Norwegian and British legal firms. The negotiations were rather intense as both sides were afraid of their national governments’ interference. A number of companies and countries were named in the exchange correspondence, as the two sides were intertwined in deals worth millions of pounds sterling. Problems arose when the British shareholders realised that they might lose control of a North American company engaged in important government contracts – Canadian Explosives Ltd. The British owned 30 percent but they had to buy out the Germans who owned 20 percent. The Trust’s North American ‘friends’ paid the British debt to the Germans and the North American friends were to be reimbursed at the end of the war.

The two sides debated the exchange of ‘cash’ (as opposed to bank securities) and the question of interest. There is evidence that the British and the German chairmen of the two Trusts were communicating directly in 1915 and were discussing the possibility of a direct meeting ‘licensed’ by the government in a neutral country. It appears that the actual share certificates were exchanged physically as part of the deal. Meanwhile, peace activists such as Sylvia Pankhurst and other would be delegates of the Women’s Peace Congress at The Hague were prevented from travelling. All (official and confirmed) financial differences in the exchange of shares were to be settled after the war, with interest from the start of the war.

On 15th June 1916 the Board of Trade agreed the final settlements, and the international company was finally split into its warring halves. The Germans would pay the British about 30 million Marks via the Treasury and the British would pay the Germans between £1.5 and £1.8 million via the Norddeutsche Bank in Hamburg. Any differences were to be settled after the war. The Trust in Britain was succeeded by Nobel’s Explosives Company, Limited. By 13th May 1920 the Trust was in liquidation. In 1925 the Liquidator wrote to the Home Office about a threat of legal action from the German side, as the shares of the Canadian Explosives Company handed over in 1915 had still not been paid off.

The Trust made huge profits during the war. Reports of the Annual General Meetings of shareholders, published in The Economist, reveal how profits increased every year of the war. It was able to pay their shareholders between 5 percent and 15 percent dividends; some with bonuses, all tax-free. The profits were all ultimately derived from the taxpayers of the nations buying arms from the Trust. In 1916, the Nobel’s Explosives Company chairman, Sir Ralph Anstruther Bart (formerly the chairman of the entire Trust) reported the success of the transaction by which the Germans were paid for their returned British shares. The balance sheet presented at the fortieth annual general meeting showed ‘a fresh start’ with ‘accumulated reserves of £1,136,000 plus an extra bonus to all shareholders already received at 20 percent on their former holdings in the Trust company.’ The recommendation was 10 percent dividends on ordinary shares, plus 5 percent dividends on preference shares plus a bonus of 5 percent! All dividends were tax-free. Bart gloated, ‘you will admit [this] is a considerable concession in the present state of income taxation.’ He indicated that as they were now working in the ‘national interest’, they were ‘entitled’ to tax free income!

The Nobel Dynamite Trust, however, is not an aberration in the history of arms companies. We can look towards the Harvey United Steel Company, (1901-1913) which exploited the patents for the manufacture of steel and armour plates in every advantageous country. On the 27th May 1902 its Board of Directors included seven British individuals, three French, one Italian and two German. Two chairmen on the board were Mr. Albert Vickers and Sir W. G. Armstrong. These men also owned shares in a torpedo factory in Hungary and had strong connections with various sites in Italy. Such arrangements were often protected by the exercise of political leverage within the heart of Government. Sir George Murray, a Director of Armstrong Whitworth and Co. was once the permanent Secretary to the Treasury, while Sir Arthur Trevor Dawson, a Director of Vickers, was also a late experimental officer at Woolwich Arsenal; a state armoury.

The exchange of correspondence in the National Archives suggests that the Trust had a huge influence on the politicians. The international nature, and the economic power, of such companies meant states were at a loss to control the effects of their own money. However, was it really the statesmen who truly lost out? The Union of Democratic Control published a pamphlet in 1915 entitled The International Industry of War and they described the arms industry as ‘injurious to working-class interests.’ Taxes that could have been spent on health or education were spent on arms to fuel wars in which only shareholders profited. (Read more about financial entanglements between British arms firms and Britain’s antagonists in the Ottoman Navy Scandal and the Vickers & Krupp case studies.)

The arms industry exists to sell weaponry. If it is allowed to sell to opposing countries, it will, whether those sides are in tension or actual conflict. Sadly, it is the norm for these sales to be allowed. Similarly, if UK-based companies are allowed to sell arms to countries that could be antagonists in the near future, they will. Buying governments might just change their mind and decide to act against the UK, or there might be a change of government. The potential for actions against UK forces is the same.

The 2011 war in Libya saw arms from one company in use by Gaddafi’s forces, the Libyan rebels and the UK and French military. The company was MBDA, a missile producing joint venture between BAE Systems, Airbus and Finmeccanica.

In 2007 Gaddafi awarded MBDA a £199 million contract for Milan anti-tank missiles and communications systems. The deal was agreed soon after then Prime Minister Tony Blair, accompanied by Guy Griffiths of BAE/MBDA, visited the country and signed an ‘Accord on a Defence Cooperation and Defence Industrial Partnership.’

- During the 2011 war, Qatar supplied MBDA’s Milan anti-tank missiles to the Libyan rebels in Benghazi.

- Both UK and French forces used MBDA cruise missiles during the war (the same missiles are called ‘Storm Shadow’ by the UK and ‘SCALP’ by France. In addition, around 230 Brimstone air-to-surface missiles were fired by the UK military, prompting the MoD into new orders to replenish depleted stocks.

As MBDA’s CEO said, ‘2011 was an excellent year for MBDA on an operational level, both for the programmes in production and for those in development. We received very positive feedback from the military campaigns in Afghanistan, Libya and the Ivory Coast about MBDA equipment and the support provided for the armed forces. For MBDA, all of these successes go towards confirming the confidence our customers have in us when it comes to the setting up of a single European prime defence contractor.’

Normal sales practice

The MBDA-Libya example is striking in that the same company is known to have supplied all sides. As information about specific deals often does not make it into the public domain, the closest we usually get to this is information on national governments promoting, or at best allowing, the sale of arms to both sides.

Sadly, this is normal. In addition to Libya, known examples of the UK providing arms to both sides include:

UK weaponry was used by both Iran and Iraq during the 1980-88 war: Iran had 875 Chieftain tanks by the time the Shah of Iran was overthrown in 1979; Iraq continued to receive UK military equipment during the war. Pakistan and India have been steady customers for UK weaponry. Sales continued regardless of the 1999 Kargil War and the stand-offs in 2001-02 and in 2008, the latter following the Mumbai attack. Both countries have been categorised by the UK government as ‘priority markets’ for arm sales, sometimes at the same time! The UK sold weapon to both Russia and Georgia prior to the conflict in August 2008. Despite the tensions between China and Taiwan the UK has sold, and continues to sell, a wide range of arms to both countries.

Arms to UK antagonists

All arms sales carry the risk of being used against the supplier’s forces or becoming part of an antagonists arsenal. In some cases it is obvious that there is a serious risk. In other cases, the risk might seem small, but weapons can last decades and it is impossible to know how they will be used.

Blatant examples are the Libya experience, as above, and arms to Argentina. UK companies supplied Argentina with a wide range of arms during the 1970s and early 1980s, both before and after the 1976 military coup. This included surface-to-air missiles, a Type 42 destroyer, Westland’s Lynx helicopters and naval radar. Staggeringly, the Ministry of Defence approved a delivery of naval spares to Argentina just 10 days before the 1982 invasion of the Falklands.

In contrast to Libya and Argentina, where ‘allies’ became enemies, there is also the potential for regime change and weaponry transferring to the hands of antagonists. The Shah of Iran was one of the UK’s main arms customer prior to the 1979 revolution then, suddenly, there were hundreds of Chieftain tanks in the arsenal of a revolutionary Iran opposed to the West.

With UK arms being licensed to around 100 countries each year – essentially to anyone who has the money, wants to buy from the UK, and is not under a multilateral arms embargo – these risks are substantial. Revolution in other major UK arms markets such as Saudi Arabia is far from inconceivable.