In the run up to the First World War not all in government prioritised spending on the military as the debate in the run up to the Finance Bill of 1905 shows. None the less, the private arms companies’ best customer was the state and private firms were accused of influencing rearmament by fomenting war scares in the run up to the First World War.

During the war the government established the Ministry of Munitions to ensure a sufficient supply after the existing private and state owned facilities failed to deliver enough shells to feed the guns. The Ministry recruited businessmen and brought hundreds of new works into operation. They succeeded in increasing the supply of arms, enriching many companies along the way. Attempts were made to control excessive profits through the munitions levy and the excess profits duty, with varying degrees of success.

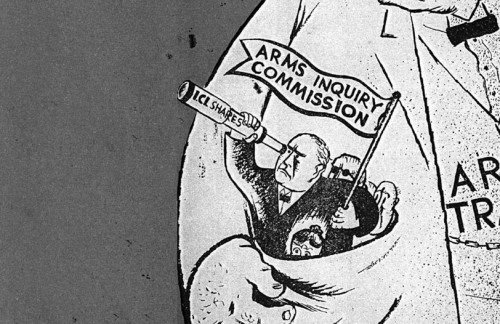

After the war, many believed that if arms were to be made the state should be the only one to make them. Pressure to prohibit the private trade in armaments led to the arms trade being put on trial in the Royal Commission on the Private Manufacture of and Trading in Armaments in 1935. The private arms companies were strongly supported by some in government, and in the midst of rearmament for the next world war the Commission’s recommendations were buried.

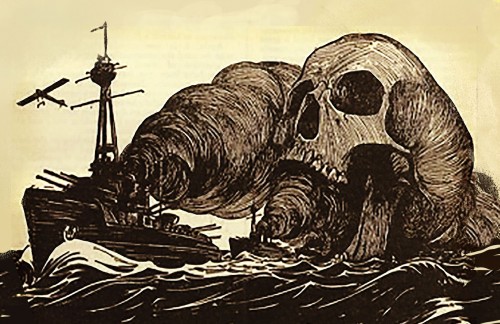

In 1909, a scandal, which was to become notorious as the Big Navy Scare, ‘swept the country off its feet.’

It was June 1927. Two of Britain’s largest arms firms, Vickers and Armstrong, were operating at 40 percent capacity, with heavy losses, and Armstrong was in massive arrears to the Bank of England. A merger scheme was pushed through at the taxpayers’ expense.

The Commission was probably the closest Britain has ever come to banning the private sale of arms. Despite its importance, its recommendations were buried at the time and are little remembered today.

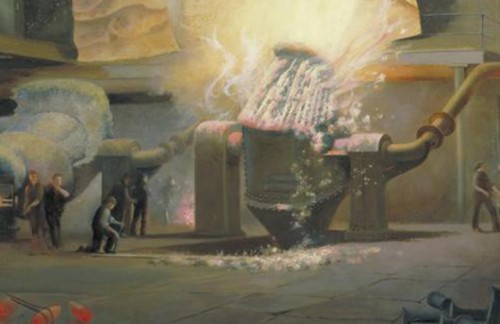

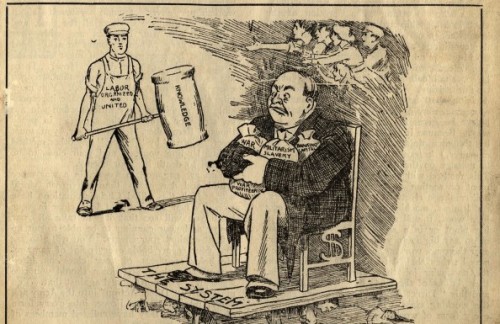

In this case study, a steel producer complains his patriotism is being exploited by an unequal system of taxation, restricting his profits. Did the government control profits effectively during the war?

As Parliament debated the 1905 Finance Bill Liberal politicians argued to reduce defence expenditure, arguing that government funds should be diverted towards social reform. In the 1906 General Election the Liberal Party won a majority, and subsequently introduced wide ranging ed...

In 1915 the Ministry of Munitions was created to oversee and increase production of armaments for the war. Many businessmen were recruited to run the new ministry, yet production was brought under greater state control than ever before. Did the way the Ministry was staffed benefi...

Opposition to the arms trade and the war many believed it had created was difficult for ordinary people. Civilian industries contracted so many were compelled by economic necessity into armaments factories and other war-work. The Munitions of War Act (1915) suspended trade union rights, and made strikes or quitting a job without employer permission illegal. Strikes were commonplace, but mainly concerned shop-floor issues. In Glasgow, the most concentrated munitions centre, workers protested profiteering and dilution by withholding labour. They were supported by socialists like Helen Crawfurd, James Maxton and John Maclean; all explicitly opposed to militarism. In London, Sylvia Pankhurst exposed poor conditions and sharp practices in the Workers’ Dreadnought, and was threatened with libel by a private arms firm. The Defence of the Realm Act was another piece of emergency legislation, granting the government sweeping powers to censor and punish critics like E.D. Morel.

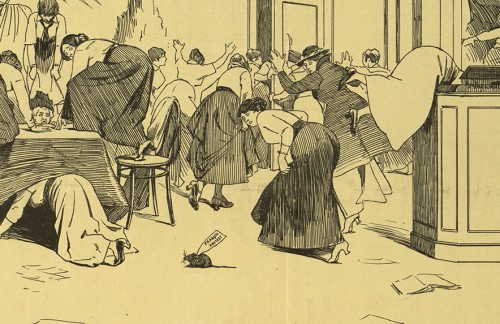

In 1915, ‘peacettes’ braved mine-strewn seas to attend the first International Women’s Peace Congress. The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, born from this Congress, lobbied for disarmament in the inter-war era (Feminists take on the World Disarmament Conference) and are still going strong today. North Wales women were especially active, rallying 2000 women on an epic peace pilgrimage. From 1921 the absolute pacifist No More War Movement (precursor to the Peace Pledge Union), pushed for Britain to lead by example and disarm completely.

Perhaps the most impressive direct action against the arms trade was spearheaded by the Hands off Russia! movement. London Dockers boycotted the SS Jolly George in 1920, which prevented weapons being shipped to anti-Bolshevik forces.

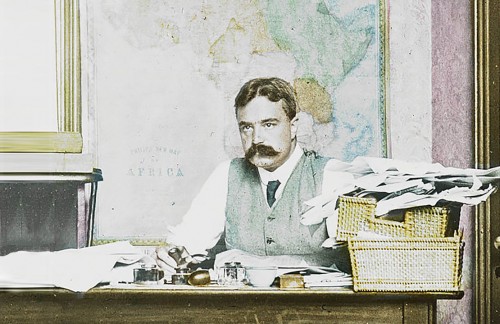

‘The monster of militarism had mastered the diplomats,’ intones the policy pamphlet of the Union of Democratic Control (UDC) whose Secretary, Edmund Dene Morel, was severely disciplined for his anti-arms trade views.

‘I am not here, then, as the accused; I am here as the accuser of capitalism dripping with blood from head to foot,’ thundered John Maclean in his famous speech from the dock, in 1918. Acting as his own counsel, Maclean launched a Marxist indictment of the arms trade and the ...

In 1910, Keir Hardie, Scottish leader of the Independent Labour Party (established in 1893) urged a general strike, and especially strikes in the arms and transport industries, should war be declared.

In preparation for the conference that was to pose a great threat to its existence, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) gathered the signatures of six million anti-war individuals.

‘Everyone is speaking of war as if it were a dispensation from the Almighty, something like measles, that we cannot avoid,’ declaimed a member of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) in 1914.

Sylvia Pankhurst - artist, activist, publisher - fought tirelessly against militarism and inequality, particularly in the East End of London.

‘When everything goes wrong, I almost prefer it to a smooth passage,’ wrote activist and Liberal MP Arthur Ponsonby, a sombre man with a high forehead. Just as well, for the late 1920s and early 1930s were a bumpy ride.

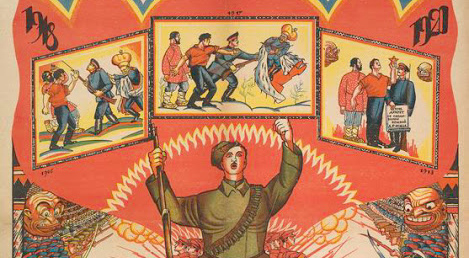

Hands off Russia! emerged in 1919 to organise opposition to British intervention on the side of the White armies in the Russian Civil War, following the Bolshevik revolution of 1917.

Many women in North Wales were active in campaigns for peace and disarmament in the late 1920s and early 1930s, whether by marching across the country in the Peacemakers’ Pilgrimage or collecting tens of thousands of signatures for the Disarmament Declaration. Discover more thr...

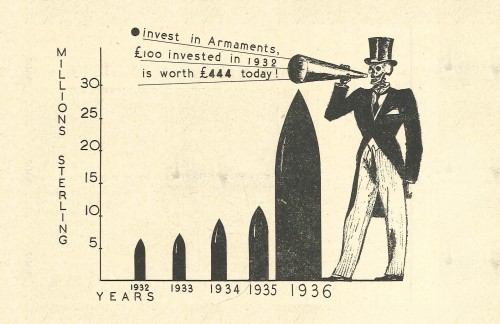

From circa 1900, a global network of private companies and multi-national trusts traded in weapons and patents and sold weapons to pretty much anyone who would buy them. Many armaments firms merged and the market became dominated by a few large companies. In Britain, the major firms were Vickers, Armstrong, Coventry Ordnance Works, John Brown, Hadfield’s Ltd, Cammell-Laird and William Beardmore. Brothers in Arms co-operated within an armaments ring to extract better prices from the War Office and Admiralty. The armaments race from 1910 (earlier for the navy) ramped up profits and dividends for shareholders, including some prominent politicians. British shareholders profited from British deaths during the war.

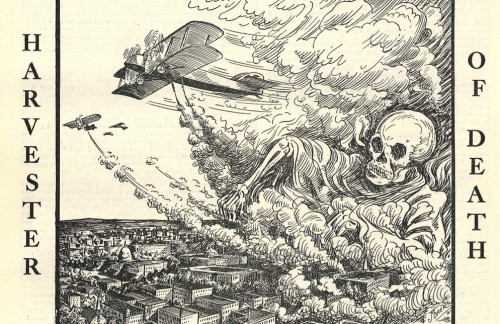

In the first global conflict since the Industrial revolution, mechanised weapons led to devastating casualties. Attempts were made to ban Chemical Warfare as early as 1899, but gas killed 25,000 on the Western front alone. Munition workers at home, mainly women, risked TNT poisoning in factories like Quedgeley Ammunition.

In 1918, the majority of workers were cast aside, despite efforts in Queensferry, North Wales and London to ensure alternative work was provided. Predictably, women were the first to join the dole queue. In the years following the Armistice, the government ran down the state sector and bailed out the private sector. BAE systems – the UK’s largest arms firm today – absorbed Vickers-Armstrong and other inter-war companies. Another feature of the post-war period was Birmingham Small Arms Company Peddling Surplus Guns throughout the world’s conflict zones.

Shells bought by the British government included a hefty royalty payment to Germany's chief armaments firm. It soon proved embarrassing.

Guns made by Birmingham Small Arms Company (BSAC) cut across ideological lines.

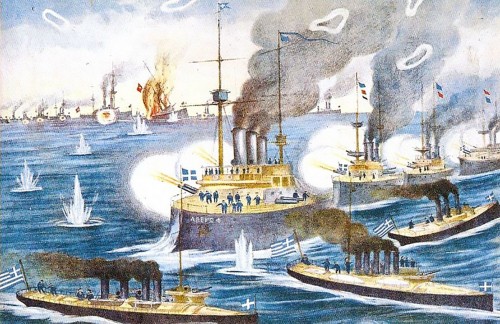

Following the Young Turk revolution of 1908, the Ottoman Empire determined to replenish its crumbling navy with the aid of gold coins, jewels and necklaces donated by citizens.

‘England is a jewel worth the rest of the world. A dynamite company there would have the entire Empire as its market.’ These are the words of the man who ended up giving his name to the Peace Prize.

The massive, government owned production facilities created during the war to make arms, presented an opportunity to create jobs and housing once the war was over.

The Great War was the first conflict in which chemical weapons were used on a large scale. 124,208 tons of gas was used in attempts to break the stalemate of trench warfare. Gas claimed half a million casualties (25,000 of these fatal) on the Western front and an unknown number i...

Huge numbers worked at the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich during the war; 63,940 were employed just before the Armistice, of which 24,360 or 38 percent were women. Unsurprisingly, after the war the workers at the Arsenal wanted to save their jobs, and a “Peace Arsenal” campaign ca...

In 1921, a League of Nations Commission on the private manufacture of arms concluded that before the First World War arms firms fermented war scares in order to sell more arms. In addition, arms firms organised international armament rings to keep prices high by playing countries...

Following the shell crisis of June 1915 local Munitions Committees were organised throughout the country in a drive to increase weapons output. The filling factory at Quedgeley was part of this network.

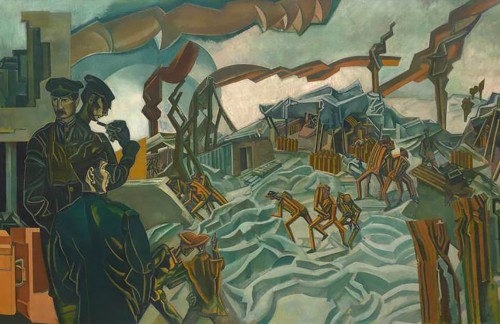

Artists like Paul Nash and John Singer Sargent brought back the “bitter truth” of the war through their art, showing the horrific impact the weaponry sold by arms companies wrought. Critical cultural works did not always receive official approval, especially while the war was ongoing; Major Barbara and The Devil’s Business, both plays about the arms trade, had very different receptions because of the different times in which they were written.

The First World War had an enormous impact on popular perceptions of the arms trade, as shown by Major-General Maurice’s writing in the aftermath of the war, read more in 'What a Waste'. Maurice did not represent a minority view, as shown by the 1935 Peace Ballot, in which 38 percent of the population voted. Over 90 percent of those polled wanted the private trade in arms to be banned.

After the First World War whether or not to continue the costly trade in armaments was a burning issue. Economic hardship was widespread and the horrors of war were fresh. Many called for disarmament, even some who had been part of the political and military establishment during ...

Famous portraitist, John Singer Sargent, turns his attention to portraying the horrors of war in its final months, producing a stark tribute of remembrance.

"What on earth is the true faith of an Armourer? To give arms to all men who offer an honest price for them, without respect of persons or principles, to aristocrat and republican, to nihilist and Tsar, to capitalist and socialist, to burglar and policeman, to … all nationaliti...

"I am no longer an artist interested and curious, I am a messenger who will bring back word from men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on forever. Feeble, inarticulate, will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth, and may it burn their lousy souls." Paul Na...

Over the winter of 1934 - 1935, half a million volunteers went from door-to-door asking the public what they thought about armaments. It was described as ‘a howling success’, producing a thumping majority in favour of disarmament.