Steel and munitions in the district

On 18th May 1915, the Mayor of Swansea wrote to David Lloyd George, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, asking him if he would visit his city. As he explained:

… Swansea and the District teem with Works of various kinds, a large number of which are engaged in the production of armament[s] and munitions, and I feel that if you could see your way to come here, your visit would, undoubtedly, have a highly beneficial and stimulating effect in connection with these manufactures.

Mayor of Swansea, in a letter to David Lloyd George

Swansea was at the heart of the South Wales steel industry. At the beginning of 1914 the industry was threatened with recession as a result of competition from abroad, particularly from Germany and Belgium. This was turned on its head when war broke out. Steel became essential to the war effort, and new business opportunities abounded.

Although Lloyd George did not visit Swansea in the end, he did attend a meeting with representatives from Swansea’s engineering and metal trades in Cardiff on 11th June 1915, organised by the newly formed Welsh National Committee for Munitions of War. Following this, a general meeting of the South Wales Employers’ was held in Swansea, and a sub-committee was formed to establish a National Shell Factory in the town. The management was formed of representatives from various local works and Masters’ Associations.

Engineering workshops belonging to Messrs. Baldwins Ltd, in Landore, Swansea, were offered for the purpose, free of rent. The factory opened later in the year producing 18 pounder and 4.5 inch shells and, in addition, it acted as a clearing house for shells in an unfinished state, which were being turned out by numerous works in the surrounding district.

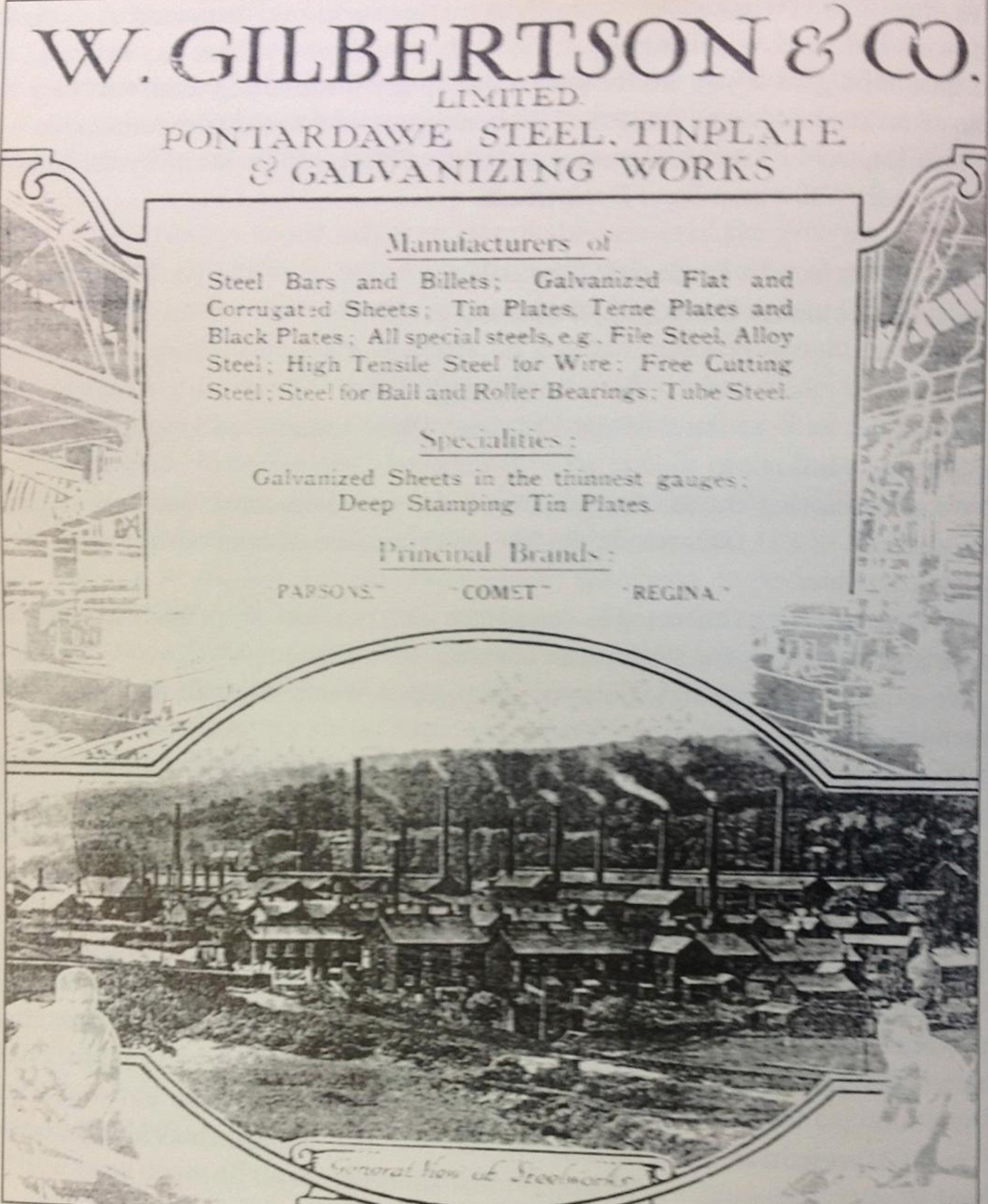

Frank Gilbertson, one of the members of the Board of Management, was Director of W. Gilbertson & Co. Ltd, a steel and tin plate manufacturing works in Pontardawe, a small town in the Swansea Valley. He was a prominent figure and spokesperson for the South Wales sheet steel and tinplate industries.

Consequently, from 1916 to 1918, he was appointed as Chairman of the South Wales Steel Allocation Committee, which was responsible for coordinating the distribution of all steel orders throughout South Wales during the war. As well as being on the Board of Management of the Swansea National Shell Factory, he was managing the Cyfarthfa (Merthyr Tydfil) Iron & Steel Works for the Ministry of Munitions.

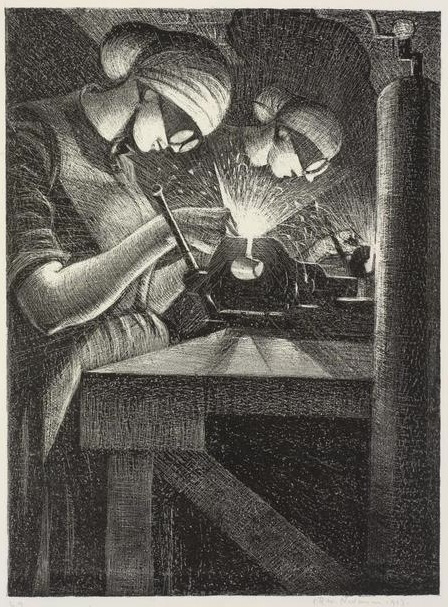

Throughout the war, W. Gilbertson & Co. produced shell steel, boiler tubes, gas bottles, steam pipes, gun parts, ingots and high carbon billets, tinplate bars, sheet bars, tinplates, blackplates and galvanized sheets. Indeed, during this time the company was, ‘almost entirely engaged in Government work’. Prior to the war, only five or six steel firms in the UK had experience in the manufacture of shell steel, which required particular knowledge and skill.

The War Office specified that steel produced for the manufacture of shells must be made by ‘the acid process’ rather than the ‘basic process’, although the latter was later permitted. W. Gilbertson & Co. adopted the acid process, attracting a good price for its shell steel. However, the Company had difficulties in acquiring raw materials of sufficient quality and quantity. The shortage of gas coal required for the production of high quality steel, for example, resulted in Gilbertson and other manufacturers purchasing collieries themselves in order to ensure supplies.

As a consequence of its involvement in war production, Gilbertson’s Works were declared a ‘controlled establishment’ in November 1915. This meant that both the activities of the company and its workforce were subject to the control of the Ministry of Munitions. It also meant, under Section 4 of the Munitions of War Act, 1915 that unlike companies not under control, Gilbertson’s was subject to a ‘munitions levy’ on its profits.

Companies that were not ‘controlled establishments’ like Gilbertson’s had their profits taxed under a different system. The Finance Act, 1915 introduced an Excess Profits Duty (EPD) which applied to all trades and businesses not under the control of the Ministry of Munitions and where their profits exceeded their pre-war standard profits by £200 or more.

The EPD was initially set at 50 percent which, although it would later increase, meant that a firm could retain its stipulated pre-war standard profit together with 50 percent of its excess profits. In contrast, the Munitions Levy allowed a firm to retain its stipulated standard profit together with just one fifth of that standard profit.

When the Munitions Levy was introduced, a special department of the Ministry of Munitions, headed by Owen Smith, was set up to administer it. Frank Gilbertson had a considerable correspondence with Owen Smith and the Ministry of Munitions. His main concern was what he considered to be the unfairness of the situation and the implications for his firm’s competitiveness and profit margins. It was not the policy of control he objected to, but the fact that not all steel works engaged in tin bar and billet production were subject to control. This, he argued, put him at a disadvantage compared to other firms.

In a letter to Owen Smith, Gilbertson expressed his views on this in no uncertain terms:

‘I quite appreciate the fact that the Chancellor of the Exchequer is likely to continue Excess Profits Duty beyond July 1st 1915, but my contention is that for any period subsequent to that date the Excess Profits Duty will have to be much greater than 50 percent if the firms controlled under the Munitions’ Act are not to be placed, relatively in a very much worse position.’

Gilbertson points out that before 1915 large profits were not made in his industry, although now they very much were. He warned, ‘The fact is quite patent that the Uncontrolled Works today, if the 50 percent profit duty is not greatly increased, will have a very much larger sum to handle as net profits in 12 months’ time, than those who are under control.’

The reasons he argued against this were:

- Uncontrolled works would accumulate a “War Fund” through saving money during the war. With this, they would be better able to deal with the increased competition from German and American industry.

- The workers in uncontrolled industries knew that the owners were making large profits and ‘are therefore disposed to claim their share in the common prosperity, which results in unnecessarily high wages and high prices, increasing the cost of the War and unfitting them for the serious times of the international competition ahead of us.’

This meant that:

‘So far, the only Works in our industries that are under control are those that were actuated by a patriotic desire to adapt their plants and educate their men for the production of special products that they foresaw the nation would need.’

Despite these anxieties, the Munitions Levy was merged with the Excess Profits Duty in 1918, and the tax was raised to 80 percent. Gilbertson’s managed to make money; their tax returns for the year ending 26th May 1917 show an estimated net profit of £99,803. Profits averaged £78,373 for the three years on which the 1918-19 income tax assessment was to be based. Perhaps the fact that steel maker and head of the Port Talbot works, Charles Wright was setting the price of steel at the Ministry of Munitions helped matters somewhat.

In a letter to the Capital & Counties Bank Ltd in Swansea, written on 25th February 1918, Frank Gilbertson states that, ‘Our Steel Works has largely increased in production during the War, probably by 80 percent, and, with the increased value of material, the working capital required to carry on operations will have to be larger after the War than it was before.’

In the same letter, he informs the bank that he has been instructed ‘to commence an Extension of our Works, which will prove a new industry for the District of a rather an important nature’.

This turned out to be a mill for rolling alloy steel round bars for artillery shells but the war ended before the works came into operation’. And, as historian P.W. Jackson points out, ‘Post-war expectations of continued industrial growth were to be dashed. By the end of 1920 the slump in Britain’s staple industries was the prelude to fifteen years of industrial stagnation, severe unemployment and corrosive poverty’.