Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, was warned that these companies ‘might be driven out of business’ and ‘their resources might no longer be available to the government in an emergency.’ In response, an Armament Firms Committee was immediately formed which included Winston Churchill (Chancellor of the Exchequer), the Lord Privy Seal, the Secretary of State for War, the Secretary of State for Air, the First Lord of the Admiralty, the President of the Board of Trade and the Secretary to the Committee.

| Position | Individual |

|---|---|

| Chairman | Winston Churchill, Chancellor of the Exchequer. During the preceding war years he had held other cabinet posts as Minister of Munitions, Secretary of State for War and Secretary of State for Air |

| Lord Privy Seal | James Edward Hubert-Gascoyne, Lord Salisbury |

| Secretary of State for War | Sir Lamington Worthington-Evans, who had been parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Munitions 1916-1918, he also had financial skills. |

| Secretary of State for Air | Sir Samuel Hoare |

| First Lord of the Admiralty (or representative) | 1st Viscount William Clive Bridgeman was one of Stanley Baldwin’s closest allies. He had a reputation for harshness and resolve. |

| The President of the Board of Trade | Sir Philip Cunliffe-Lister, 1st Earl of Swinton |

| Secretary to the Committee | R.B. Howorth |

Winston Churchill in a bathing costume, date unknown/Wikimedia Creative Commons

Winston Churchill in a bathing costume, date unknown/Wikimedia Creative CommonsEach department within the Committee examined a plan to merge Vickers and Armstrong drawn up by William Plender, accountant. In Plender’s scheme, both firms were to be issued with share capital – effectively a subsidy at the taxpayers’ expense – and retain some of their existing works and yards. By the end of July the three service departments opposed to Plender’s fusion proposal had given their written responses.

Churchill, however, did not appear to pay attention to them. A revealing note in the opening contents page of the Report’s Proceedings and Memoranda (a listing of all documents relating to the fusion scheme up to 29th September 1927) stated that the ‘the Chairman [Churchill] decided, after considering the views of the departments concerned, and, owing to the emergency of the matter, to acquaint the Governor of the Bank of England with the views of the government.’

By answering on their behalf Churchill had taken it upon himself to agree to the merger proposals declaring that his views were not ‘inconsistent’ with theirs. To describe the matter as an emergency in July 1927 was probably a red herring: the Bank of England had known of Armstrong’s situation for a number of years as the company owed it £2.6 million (sterling).

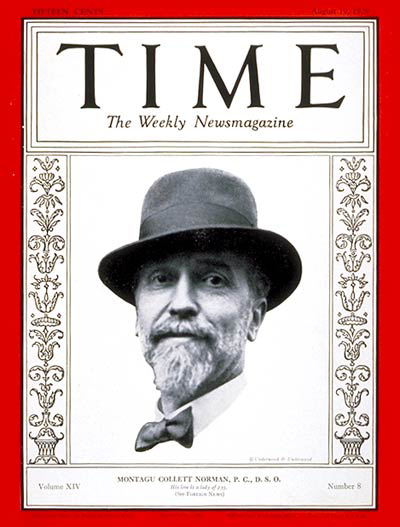

The committee were apparently unable to meet before summer recess. As Churchill did not want the authors of the scheme ‘to be held up over the holidays,’ Churchill’s letter to the Governor of the Bank of England (Sir Montagu Collet Norman) stated that they were ‘anxious to encourage amalgamations such as that proposed,’ even though the other government service departments had not agreed to Plender’s fusion scheme. This meant that alternative proposals, such as Vickers and Armstrong renting works retained by the government, were rejected by Churchill.

Sir Herbert Lawrence/© National Portrait Gallery London. Creative Commons Licence. http://tinyurl.com/nebswmg

Sir Herbert Lawrence/© National Portrait Gallery London. Creative Commons Licence. http://tinyurl.com/nebswmgThe Admiralty thought that the only essential sites owned by Armstrong were the Elswick Ordnance works at Newcastle and the Thames Ammunition works at Erith; the facts as presented to them did not warrant the proposed merger. Instead, the Admiralty proposed that Vickers buy the aforementioned sites, since Vickers’ finances had been effectively rationalised by accountants Plender and Jenkinson in previous years.

A note by the Secretary of State for Air (25th July) stated that Vickers and Armstrong were only ‘two out of some 17 firms which manufacture aircraft for the Royal Air force.’ He, like his Admiralty and Secretary for War counterparts, were wary of setting precedents for other arms firms and preferred a definite programme of orders over a number of years. But the necessary contingency plans to keep the armaments staff efficient in the ‘absence of orders’ had not been drawn up.

The service departments viewed Plender’s merger proposal as a subsidy to Vickers and Armstrong but Churchill ignored this and their lack of support: he was following Plender’s memoranda (published on the 22nd June) to the letter. Before the Armaments Committee had even been formed Plender had stated the only way forward: ‘it cannot be too strongly emphasised that Messrs Vickers and Armstrong are primarily manufacturers of armaments and must continue to be so unless the vast skill and experience attained is to be lost to this country.

In the opinion of both firms and their advisers, fusion coupled with the co-operation of the British government, somewhat along the lines suggested in this memorandum, is the only solution.’ The merger was a shareholders’ and accountant’s forgone conclusion.

Sir Otto Ernest Niemeyer/© National Portrait Gallery London. Creative Commons Licence. ttp://tinyurl.com/p29bt8u

Sir Otto Ernest Niemeyer/© National Portrait Gallery London. Creative Commons Licence. ttp://tinyurl.com/p29bt8uThe valuations of both companies’ fixed assets were taken by looking at their land, plant and machinery, buildings, loose tools, fixtures and fittings, residential properties and the maintenance of plants, works and tools. They applied a heady concoction of figures and accounts from various dates and depreciation rates. For example, for plant and machinery Armstrong was assigned their 1920 valuation with a seven and a half percent depreciation rate up to December 1926, while twelve year old figures were employed for Vickers by using their 1914 valuation for the company with a 15 percent depreciation rate up to 1919 and a seven and a half percent depreciation rate thereafter.

Once the total fixed assets for each company (excluding goodwill) had been calculated and the deficiency in earnings had been subtracted Vickers was valued at £4,081,700 and Armstrong was valued at £3,421,600. It is probable that the accountants’ method of valuation concealed the fact that Armstrong was in debt to the Bank of England. From the 1st January 1928, the newly merged companies would not take on the debts owed by both of them as vendor companies, the debts were to be discharged and paid by Vickers and Armstrong respectively.

The purchase price for each company was represented as shares for their fixed assets which were issued as fully paid up: £8.5 million went to Vickers (£2 million in A preference shares, £1.5 million in B preference shares and £5 million in ordinary shares). £4.5 million shares were issued to Armstrong (£2.5 million as B preference shares and £2 million as ordinary shares). The division of shares issued to each was based upon the potential earning capacity of Vickers compared to Armstrong, so the estimates were not really based on reality.

In the summary of the provisional agreement for the amalgamation (31st October 1927) it was stated that the initial share capital of the new company would not exceed £21 million in total (£629 million in 2005 money). In effect, by issuing fully paid up shares, the Bank of England was writing a credit note for the existing shareholders and allowing the company to start again under a different name. Conveniently the government had also just passed Clause 53 of the Finance Act, which lessened the burden of capital and transfer duties incurred ‘on such amalgamations.’

The new company, Vickers-Armstrong Ltd., had a profits insurance contract with Sun Insurance which was to run for at least five years from February 1928. Montagu Norman, Bank of England director, used the Sun Insurance Company to obscure the fact that this was a government bailout of the private sector. If the newly merged company did not make £ 900,000 profit per year then Sun Life would pay a yearly contribution to their profits of up to £200,000. If profits did exceed this amount then Sun could appropriate 40 percent of the amount.

To guarantee such pay out the new company paid premiums of £2,000 per annum. By 1936 Vickers-Armstrong had received £1,000,000 which was then repayed to Sun Life as £1,116,135 (including three percent interest rate) on 31st March 1936 when the insurance contract was cancelled. Plender, the original architect of the plan, had assured all involved with the arms merger that there would be minimum profits, by hook or by crook! Vickers-Armstrong Ltd. got £ 200,000 every year for five years.

As a condition of the merger (and the government underwriting) Vickers-Armstrong was made to restrict its manufacturing to shipbuilding and heavy engineering, especially for the arms trade.

Read more about Vickers’ and Armstrong’s exploits before and during the war in the Ottoman Navy Scandal, Vickers & Krupp and Brothers in Arms case studies.

The diagram below shows the cosy relationship between Vickers-Armstrong personnel, bankers and the government.

Export Finance is a government-provided insurance scheme. It uses public money to guarantee that companies and banks involved in an export deal will not lose out if the overseas buyer does not pay, or makes late payments. Companies are charged a premium and UK Export Finance aims to break even, but any shortfall comes from the UK taxpayer. UK Export Finance (UKEF), the independent government department that provides the scheme was known until November 2011 as the Export Credits Guarantee Department (ECGD). The ECGD was established in 1919 to ‘help British exporters re-establish their trade after the First World War.’

It originally limited the provision of export credits to a named group of countries. Today, this publicly funded insurance supports international weapons deals. In recent times, the arms industry has been the largest beneficiary of Export Credit Guarantees, even though arms account for just 1.5 percent of total UK exports. Between 2007 and 2008 arms companies received a massive 57 percent of export credits.

It has supported weapons sales to dictators. BAE Systems tops the list of arms company beneficiaries: in one year (2006-7) its arms sales to the repressive regime of Saudi Arabia accounted for 42 percent of all export credit guarantees.

Export credit guarantees to arms companies declined drastically to just one percent in 2008-9 when BAE ended the support for its Saudi arms deals. This coincided with a highly critical report [OECD’s October 2008 report into the UK (PDF 739kb)] from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which criticised the ECGD for its lack of action on evidence of misrepresentations by BAE. It questioned providing export support where the recipient had interfered with criminal law proceedings as Saudi Arabia had done with the SFO inquiry.

However, backing for military deals soared again to 47 percent of all export credits in 2012-13. This included £2 billon cover for the purchase of BAE Eurofighter Typhoons by the dictatorship in Oman; £4.2 million for the export of intelligence equipment to Indonesian Ministry of Defence and £1.1 million for the purchase of hovercraft by the Pakistani navy.

It has supported the sale of weapons later used against the UK. Argentina is still being pursued for debt from loans made to the Argentine military rulers in the 1970s [http://jubileedebt.org.uk/news/unfair-debt-deal-agreed-argentina]. Some of the equipment purchased was later used in the invasion of the Falklands.

Sometimes the purchasers do not pay; then UKEF must pay instead. In October 2012 UKEF published information on Sovereign Debt. This showed debts for military equipment and projects owed by Mubarak’s Egypt, Galtieri’s Argentina and Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

CAAT is one of a number of organisations, including Amnesty International UK, The Corner House, Jubilee Debt Campaign and WWF UK, which are working for reform of export finance as Clean Up Britain’s Exports.