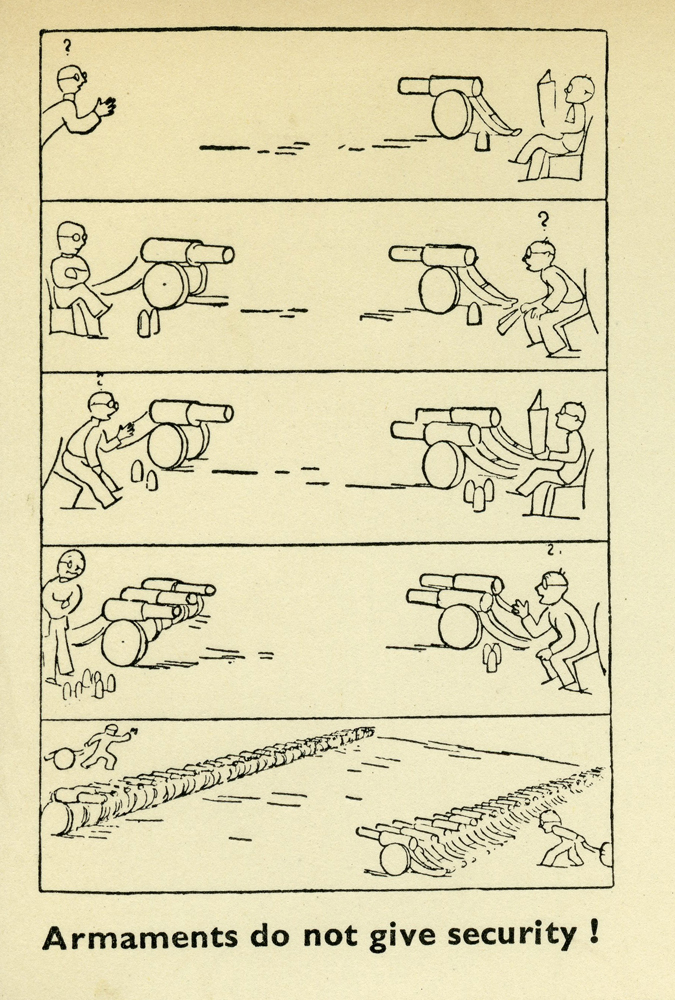

Unless civilization can break with armaments, armaments will break civilization, from 'No More War', July 1924/© Peace Pledge Union Archive

Unless civilization can break with armaments, armaments will break civilization, from 'No More War', July 1924/© Peace Pledge Union ArchivePonsonby’s No More War Movement (which replaced the No Conscription Fellowship in 1921) described itself as ‘the one pacifist organisation that offers unqualified opposition to participation in war.’ For example, on 17th March 1927, Ponsonby moved a radical resolution in the House of Commons to abolish the British air force. At its height, the No More War Movement had 94 branches countrywide. Its main tenets were as follows: disputes could be settled by diplomacy, Britain could create confidence between nations through disarmament and ‘there is no risk our nation can take for peace as great as the risk of war.’

No More War Movement wanted to spice up pacifism in order to rival the seductions of military display, such as the miniature bomb explosions at the Admiralty Theatre, Wembley, which so excited parties of school children. The June 1928 No More War (the newsletter of the Movement) cried,

We pacifists are much too dull. Our propaganda is all alike. There is no variety, no music, no colour, no appeal, except to cold logic and reason, and man is mainly unreasonable and illogical in both his thoughts and his actions.

No More War newsletter

The writer went on to suggest the following tableaux:

- A lawn surrounded with flower beds, in the corner a hammock with sleeping child, children playing while a nurse in the background looks after the wants of each.

Slogan: Disarmament means health, happiness and comfort! - A backyard with a rubbish heap in the corner; dirty unkempt children playing with mud or a heap of ruins with a wall on one side, debris with an arm, leg or head protruding.

Slogan: Armaments mean poverty, unemployment starvation or death!

‘A war emergency is very likely to arise before the organised war resistance movement either in this country or abroad is strong enough politically to prevent it. Because this is so, preparations for dealing with such an emergency will play an important part in any realistic strategy of peace.’

While the Government’s War Book instructed the public on how to prepare for war, the No More War Movement aimed to challenge the sense of inevitability. In 1932, it outlined Ponsonby’s plans for a Peace Book – a list of contacts who would help to ‘counter war preparations and expose the danger of the move contemplated before any actual declaration of the war is made. The book would hold details of an emergency officer in every town and village, assistants, recruitment officers, a press officer, public meetings organisers and local supporters. ‘Street captains’ – one on every street in the country – would also canvass residents, distribute pamphlets and announce public meetings. Public protest would take the form of refusing ‘every form of personal co-operation with an oppressive government;’ including general strikes, refusal of rents and taxes, boycott of large manufacturing and distributing firms, appeals to the police and military to destroy arms, non-violent demonstrations and the occupation of private estates on former common land. It was hoped each individual would ‘see his or her place in a plan designed to include members of every class, trade, or profession.’

The movement was also committed to non-violence and planned how it would meet any unrest that ‘might develop even from successful opposition to a war.’ Leaders intended to use strategies learned during the General Strike of 1926, when No More War organised social and educational activities, such as lectures, concerts, games in public parks and relief work.

Ponsonby wrote a Peace Letter to the Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, signed by 128,770 supporters who refused ‘to support or render war service’.

Baldwin responded to the letter by claiming that an unarmed and ‘impotent’ country would be left open to ‘hostile forces’. He also wrote that ‘the collapse of the League of Nations’ would be ‘inevitable’ as a result of further disarmament. In a second letter, Ponsonby wrote that ‘unprovoked aggression is a war myth’ and that he did not believe in the strength of security based on ‘an ultimate sanction of force’. He added: ‘so long as armaments for international conflict exist there will be competition with its inevitable consequences.’

The movement’s Organising Secretary Walter H. Ayles wrote to Baldwin: ‘How do you reconcile your desire to go buccaneering, when you think it fit, with your dictum that wars of aggression are an abomination?’ He adds: ‘Nations invite attack if they are imperialistic or allied to imperialistic nations. But a disarmed nation is powerless to grab the territory of another nation.’

‘What a travesty of the League [of Nations] which aims for ‘international peace and security by the acceptance of obligations not to resort to war, to suggest that its maintenance is a reason for keeping up national forces,’ wrote another critic, Kathleen E. Innes.

Public opinion is not enough; it must have some way of making itself more effective if any real move towards international peace is to be achieved.Lucy Cox

The movement planned to use links between its offices and Geneva to send a shower of over 1000 telegrams to the British delegation at the World Disarmament Conference in 1932. It prepared to anticipate ‘danger points’ in the conference so that branches could exert pressure in favour of a certain policy.

It also presented a petition, signed by 1,475 organisations, which called for Britain to disarm by example rather than waiting for other nations. General Secretary Lucy Cox conceded that, ‘we have a duty as pacifists to see that as large a measure of disarmament as possible [from all nations] results from the conference.’

The movement attributed the failure of the conference to ‘activity on the part of armament rings and their vested war interests.’ It concluded: ‘public opinion is not enough; it must have some way of making itself more effective if any real move towards international peace is to be achieved.’

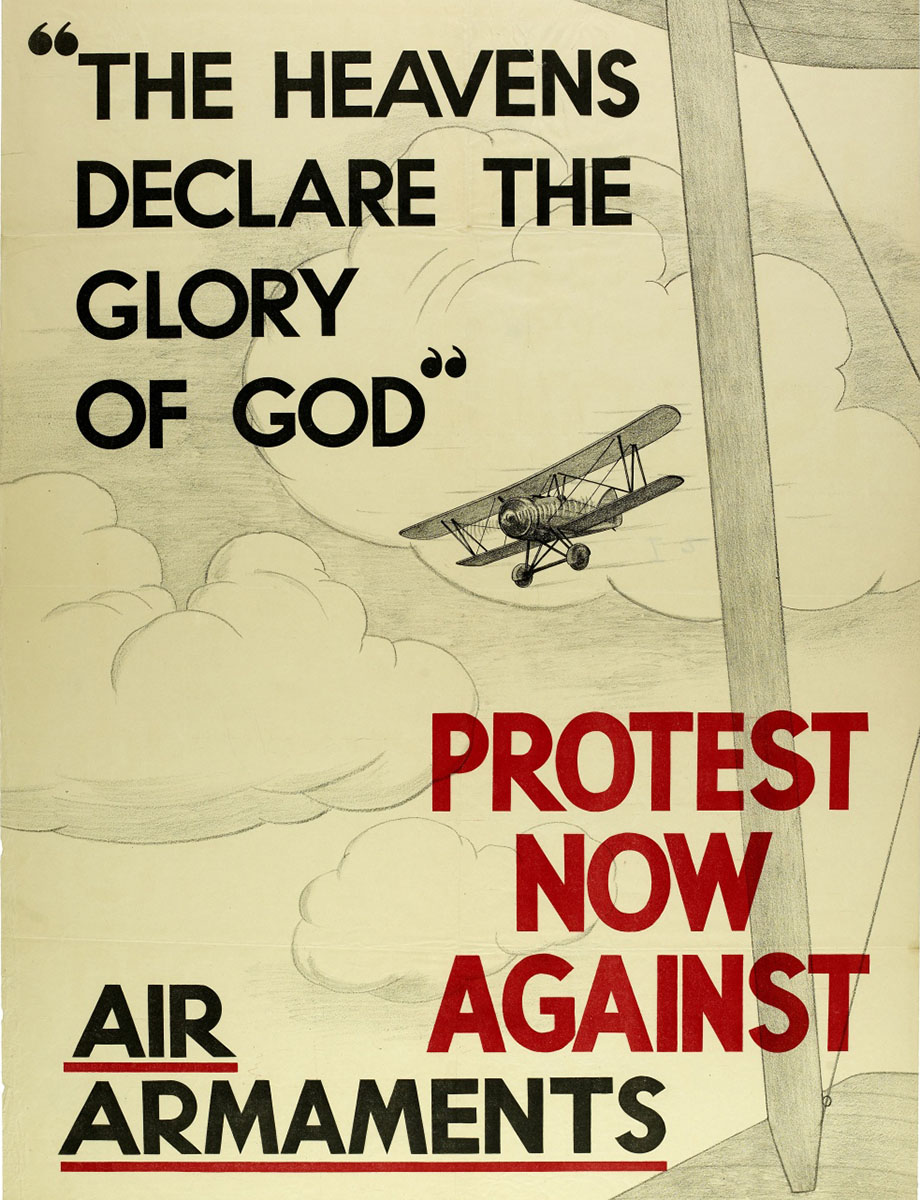

They witnessed a clash between idealism and the old style of diplomacy, in which politicians refused to reduce national armaments ‘without a guarantee of safety…found in mutual defensive agreements.’ The movement continued its commitment to complete disarmament, fearing that the principle of collective security, which was backed by other peace groups, could ‘support engagement in a new armed conflict.’ In 1934, No More War Movement fell out with internationalist Robert Cecil who proposed that the League of Nations should have a peace-keeping air force; Ponsonby refused to countenance any discussion of ‘how to wage the next war.’ (Read more about the World Disarmament Conference here).

‘It is often the total absence of a quarrel that constitutes the madness and the tragedy’, wrote William Otway McCannell in No More War, as he described his painting The Devil’s Chessboard, which satirised war as a game between the old and powerful. Lucy Cox, who described war as ‘utterly indefensible’ and joined the movement because ‘it recognises that the roots of modern wars lie in evil social and economic conditions, and strives for their removal’, left in unhappy circumstances after eight years as secretary.

She resigned in 1932 and called the group ‘a bunch of communists’ after its members were divided on whether both fascist and republican sides of the Spanish Civil War should be opposed. (Many left-wing people who were generally against war supported the republicans). Membership fell from almost 3,000 in 1934, to just 1,771 by 1936, while committee member Runham Brown said half of all branches were ‘weak and uninspiring’ due to ‘passivity’ and ‘fruitless talk’.

In 1938, the No More War Movement merged with the Peace Pledge Union, which was founded by Dick Sheppard and Arthur Ponsonby. The union launched with a postcard campaign to ‘renounce war and never again to support another’, which received 130,000 pledges, and is still going strong today. It continues to campaign for a world without war; protesting against remote-controlled drone assassinations, challenging militarism and conscription, among other things.

You can follow PPU’s project on conscientious objectors during the First World War at: www.ppu.org.uk/nomorewar