The Krupp patents debacle, which spiralled over many decades, suggested ‘national defence’ was a smokescreen for international profit making. As early as 1896, the leading German arms firm Krupp Works had been earning royalties on each ton of armour plate produced by Harvey United Steel, an international cartel which, in 1902, counted directors from British, American, French and German firms on its board. The implications of this case study are more disturbing still – German troops were torn to shreds by shells with fuzes stamped ‘Krupp Patent Zünder’ throughout the First World War.

Vickers – the second best capitalised arms firm in the UK (according to 1913 statistics) – and Krupp traded in weapons from 1902. Vickers cut deals allowing them to use the Krupp blueprints for time and percussion shell fuzes (no. 80 and no. 82 to be precise) in 1902, and for fuze-related machinery in 1908. They were contractually obliged to pay patent royalties for 15 years for each contract and communicate any improvements in design and manufacture to Krupp. Payments of royalties were contracted beyond the actual patent expiry date in 1914.

At the outbreak of war, all payments to Germany were suspended under the Trading with the Enemy Act. Vickers were supposed to deposit royalty payments with the ‘Custodian of Enemy Properties.’ The plot thickened when Vickers stopped paying royalties into that account for Krupp, while still including the royalties in the shell prices charged to the government.

Between 1914 and 1918 Vickers sold millions of fuzes to the British government; an estimated 14,139,000 fuzes of just type no. 80. By a tentative estimate from various Ministry of Munitions files, Vickers were paid by the government £10,764,000 for fuze no. 80 (£200,000,000 in 2005’s money). It is clear from just this one example that Vickers and their shareholders made handsome profits from supplying the Government’s war effort with ammunition. It is likely that the profit was tax-free.

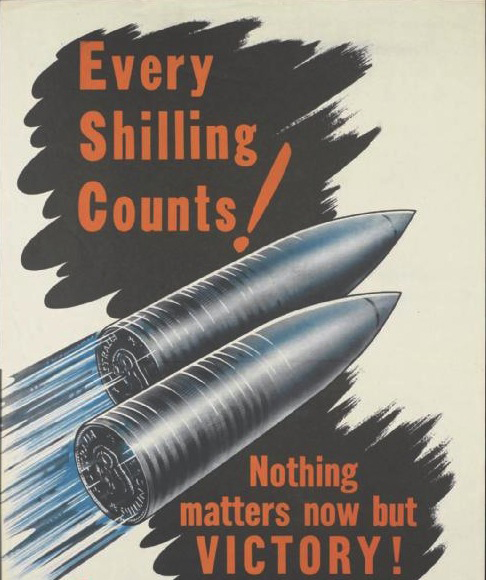

Wartime correspondence shows that Vickers did pass royalty payments on to the Government in their invoices, rather than paying them from their own profits. Contracts signed by the government included 1 shilling 2d of royalties on each fuze.

It was not until 1916 that the royalties became an obvious blunder on the government’s part (suggesting either poor organisation or a lackadaisical attitude to administration of contracts). The contracts between Vickers and Krupp were officially suspended in 1916 by the revised Trading with the Enemy Act, though lawyers puzzled over whether this was allowed under international law. At the same time, the Ministry of Munitions and Admiralty promised indemnities (up to £320,000) to Vickers against possible future post war Krupp demands.

After the contract with Krupp was suspended, the government tried repeatedly to negotiate lower shell prices with Vickers. By the end of the war, the Ministry of Munitions and the war office had already paid £300,329 royalties (calculated as a percentage of fuze prices). The government had to recover overpaid royalties from Vickers, by deducting money from the Treasury’s final post-war settlement of £1,250,000 to Vickers.

None of this prevented Vickers director Basil Zaharoff receiving a knighthood in 1919.

After the war, at The Anglo-German mixed Arbitral Tribunal, Krupp demanded over £300,000 in unpaid royalties between 4th August 1914 and 30th September 1917 plus the interest for the whole non-payment period (1914 to 1926). Despite complaints from a variety of Government institutions about the case not coming to a conclusion, Vickers’ communications were slack. They usually answered, ‘we are consulting our solicitors.’ Their argument was that the Vickers-Krupp contracts specifically stipulated their German nature and therefore the validity of its cancellation during the war. Vickers also insisted it was the government’s responsibility to pay the post-war debts. Government lawyers estimated that should the Germans win the Tribunal case, the Treasury would be liable for half a million pounds sterling, of which Vickers would only contribute £180,000.

After years of legal wrangling, in 1926, Vickers were allowed to negotiate debts directly with Krupp and agreed to pay through the British and German Clearing Offices. On 1st September 1926 Vickers paid £40,000. It seems to be quite a modest estimation of the number of shells made and fired. However, at the same time, Vickers informed the British Government they were purchasing British rights of a Clock Fuze and other patents from Krupp, which must have sweetened the blow.

Germany’s military menace in the 1930s seemed to be an overnight miracle, but rearmament had been building secretly throughout the 1920s in Switzerland and the Netherlands – neatly side-stepping the Versailles Treaty. Ironically, Vickers, which used Krupp patents in much of its weapons development, funded some of Germany’s rearmament via royalty payments.

Read about weapons sold by Vickers being used against Allied troops in the Dardanelles and about the government bailing out Vickers and Armstrong after the war.

If UK-based companies are allowed to sell arms to countries that could be antagonists in the near future, they will. Buying governments might just change their mind and decide to act against the UK, or there might be a change of government. The potential for actions against UK forces is the same.

The 2011 war in Libya saw arms from one company in use by Gaddafi’s forces, the Libyan rebels and the UK and French military. The company was MBDA, a missile producing joint venture between BAE Systems, Airbus and Finmeccanica.

- In 2007 Gaddafi awarded MBDA a £199 million contract for Milan anti-tank missiles and communications systems. The deal was agreed soon after then Prime Minister Tony Blair, accompanied by Guy Griffiths of BAE/MBDA, visited the country and signed an ‘Accord on a Defence Cooperation and Defence Industrial Partnership.’

- During the 2011 war, Qatar supplied MBDA’s Milan anti-tank missiles to the Libyan rebels in Benghazi.

- Both UK and French forces used MBDA cruise missiles during the war (the same missiles are called ‘Storm Shadow’ by the UK and ‘SCALP’ by France. In addition, around 230 Brimstone air-to-surface missiles were fired by the UK military, prompting the MoD into new orders to replenish depleted stocks.

As MBDA’s CEO said,

‘2011 was an excellent year for MBDA on an operational level, both for the programmes in production and for those in development. We received very positive feedback from the military campaigns in Afghanistan, Libya and the Ivory Coast about MBDA equipment and the support provided for the armed forces. For MBDA, all of these successes go towards confirming the confidence our customers have in us when it comes to the setting up of a single European prime defence contractor.’

The MBDA-Libya example is striking in that the same company is known to have supplied all sides. As information about specific deals often does not make it into the public domain, the closest we usually get to this is information on national governments promoting, or at best allowing, the sale of arms to both sides.

All arms sales carry the risk of being used against the supplier’s forces or becoming part of an antagonists arsenal. In some cases it is obvious that there is a serious risk. In other cases, the risk might seem small, but weapons can last decades and it is impossible to know how they will be used.

Blatant examples are the Libya experience and arms to Argentina. UK companies supplied Argentina with a wide range of arms during the 1970s and early 1980s, both before and after the 1976 military coup. This included surface-to-air missiles, a Type 42 destroyer, Westland’s Lynx helicopters and naval radar. Staggeringly, the Ministry of Defence approved a delivery of naval spares to Argentina just 10 days before the 1982 invasion of the Falklands.

In contrast to Libya and Argentina, where ‘allies’ became enemies, there is also the potential for regime change and weaponry transferring to the hands of antagonists. The Shah of Iran was one of the UK’s main arms customers prior to the 1979 revolution then, suddenly, there were hundreds of Chieftain tanks in the arsenal of a revolutionary Iran opposed to the West.

With UK arms being licensed to around 100 countries each year – essentially to anyone who has the money, wants to buy from the UK, and is not under a multilateral arms embargo – these risks are substantial. Revolution in other major UK arms markets such as Saudi Arabia is far from inconceivable.