The UDC ‘arose out of the war’ in September 1914 as a pressure group and quickly grew into a major national organisation with over sixty local branches.

It focused upon practical policy proposals to achieve ‘the establishment and maintenance of an enduring peace’ in the longer term. These included disarmament and greater parliamentary control of ‘autocratic’ Foreign Office policy. Secret diplomacy and the machinations of the private arms trade were blamed for fomenting war.

The UDC charged the private arms trade with controlling newspapers, inventing war scares, playing nations off against one another and encouraging insecurity. The organisation asserted that ‘disarmament, so far as national economy is concerned, is the ultimate condition to be wished for,’ but also felt it could not be achieved immediately. In the short term they wished for ‘drastic reduction, by consent, of the armaments of all the belligerent powers,’ as well as ‘nationalisation of the manufacture of armaments and the control of the export of armaments by one country to another.’ They approached the arms trade from an economic standpoint, claiming ‘all money spent on arms is economically pure waste.’ It differed from other industries, because it satisfied no human need.

The UDC was not an absolute pacifist organisation, but all of its leaders had opposed the declaration of war in 1914. It had links to the Labour Party (which came to accept its programme) and many members transitioned from liberalism to socialism as the extent of the Liberal government’s pre-war diplomacy became apparent. Catherine Cline even argues that the U.D.C initiated the influx of middle-class Liberals that transformed the Labour party from a narrowly working-class group to a national party. While this alliance with Labour was not cemented until the last months of the war, it was nonetheless significant, and the organisational apparatus of the Independent Labour Party (a small group on the Left wing of the Labour party) was utilised by the organisation.

The UDC leadership contained dominant political figures such as Charles Trevelyan, who resigned from government in an act of protest against Britain’s declaration of war, Ramsay MacDonald, who resigned chairmanship of the Parliamentary Labour Party when it voted for war credits, and Arthur Ponsonby, who was later active in the No More War Movement. Another founder member, philosopher Bertrand Russell, was sacked from Trinity College Cambridge and imprisoned for warning British workers to be wary of the American army, which had a reputation for strike breaking.

Before becoming Executive Secretary and the dominant political influence in the U.D.C, Edmund Dene Morel co-founded the Congo Reform Association, which aimed to expose ‘the atrocious system of slavery’ under Belgian King Leopold.

Morel was committed to ending the arms trade, claiming in his 1918 work Truth and the War that, ‘among the vested interests concerned in keeping Europe in a condition of fear and apprehension, none perhaps are more insidious and more dangerous than the interests bound up with the armament industry; and in no country are they more powerful than our own.’ He was vilified in the popular press. The Daily Express falsely depicted Morel in thrall to German paymasters, listed details of future U.D.C meetings and encouraged its readers to break them up.

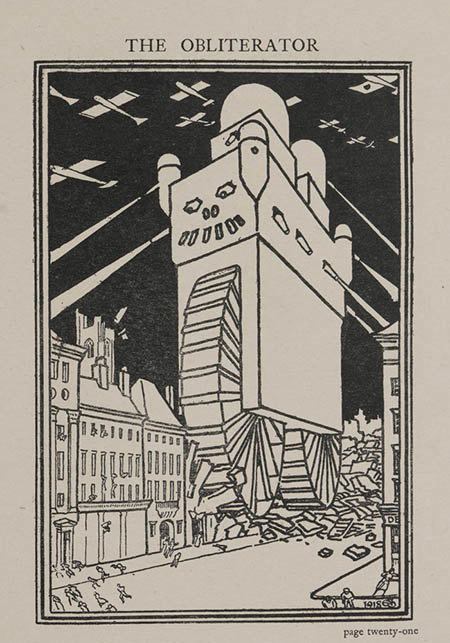

'The Obliterator,' a nightmarish vision of a weapon of mass destruction, by Quaker artist Joseph Southall, /© Reproduced with kind permission of the Barrow Family/Photo © Birmingham Museums Trust

'The Obliterator,' a nightmarish vision of a weapon of mass destruction, by Quaker artist Joseph Southall, /© Reproduced with kind permission of the Barrow Family/Photo © Birmingham Museums TrustMorel described the process of his imprisonment in a speech at a 1918 UDC reception in Glasgow. ‘The abuse to which I have been subjected has not been confined to the ordinary sort of thing which any man who takes an unpopular view of a great war must anticipate. We all expect to be called fools and fanatics, cranks and intriguers, sufferers from diseased vanity, and friends of every country but our own …’ Morel argues that the government seized on a minor infringement as an opportunity to end his publications. It is also probable that imprisoning Morel was in some way a symbolic move to intimidate other opponents, as he was a leading opponent of wartime government policy. The experience of Glaswegian agitator, John Maclean, was similar. ‘What they wanted was to get me out of the way.’ Cline claims, ‘Morel’s imprisonment had made him a hero of the British Left,’ therefore, the government was not successful if they were aiming to minimise his impact.

Quaker artist Joseph Southall, famed for his powerful impressions of nightmarish weapons, profiteering industrialists and greedy politicians, was among those protesting Morel’s imprisonment. As Secretary of the Birmingham Independent Labour Party, Southall moved a resolution to lobby the Prime Minister and Home Secretary. His satirical fable ‘The Earth and the Moon,’ does not name Morel, but is clearly directed at his cause. ‘One of the most distinguished Imperians even went so far as to publish a treatise [Truth and the War], in which he proved by theory and experiment that the real danger lay not in any attack from the moon but from the errors and greed of the magicians [lying warmongers]. This disloyal person was at once cast into prison.’

Morel’s diary reveals how imprisonment impacted upon his health, as well as his family; the stigma weighed heavily on him and his wife Mary Morel. Mary Morel received numerous letters of sympathy upon her husband’s imprisonment, from many branches and members of the UDC, the Independent Labour Party, and Arthur Ponsonby of No More War Movement, among others. Their volume demonstrates support for Morel’s views and abhorrence at curtailment of free expression. Mary Morel also corresponded with Pentonville prison officials, petitioning for her husband to be allowed to receive books (a letter sent on 13th November 1917 suggests the Pentonville Governor refused), more regular visits, and release on medical grounds. When he got out, Morel was normally reluctant to talk about himself in public, claiming ‘the incident is such a very microscopic drop in the sea of error and stupidity which surrounds us.’