The Royal Commission on the Private Manufacture of and Trading in Arms was announced by the Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald to the British Parliament on 18th February 1935. Over one year and 22 public sessions the Commission heard from expert witnesses for and against the private manufacture of arms. It concluded, unanimously, that greater state control of the private manufacture of arms was needed.

The Commission asked the public to contribute to the enquiry; in response submissions in support of banning the private trade in arms were sent from more than fifty organisations, representing more than two million people. These included the League of Nations Union, Union for Democratic Control, Labour Party, Trades Union Congress, numerous peace councils, church organisations and women’s groups.

First, the Commission heard from pro-disarmament witnesses, followed by the heads of the major arms firms, then, in strict privacy, from the relevant government departments. Importantly, the Cabinet Secretary for the Committee of Imperial Defence, Sir Maurice Hankey, expressed his support for private arms firms, and would later help to draft the 1936 White Paper on Defence which would follow (but largely ignore) the Royal Commission’s recommendations.

Historian David Anderson argues that public fascination with nefarious arms dealers waned after the First World War, with the possible exception of the notorious Vickers employee Basil Zaharoff. However, in 1933 the arms trade became a media issue once more, perhaps due to the Chaco War between Bolivia and Paraguay and Germany’s withdrawal from the Disarmament Conference.

The Labour Party argued in Parliament for the prohibition of the private manufacture of arms. On an international level the League of Nations also advocated against the private trade. When the Disarmament Conference adjourned on 8 June 1934 a Special Commission to counter the arms trade was the last remaining group left working in Geneva.

In the United States the ‘Nye Committee’ was a ‘show-trial investigation’ held from 4th to 21st September 1934 by the US Senate to investigate the arms industry. The Nye Committee received substantial press coverage in British newspapers, who were especially interested as the proceedings implicated home grown firms such as Vickers in shady deals and corruption. This increased the pressure for a similar endeavour to take place in the UK.

Unlike its American predecessor, the Royal Commission was not given powers to issue oaths or subpoena witnesses. This raised concerns that the Commission would be toothless. With its greater powers the Nye Committee was able to seize letters that would otherwise not have become part of the public domain. The scandals it brought to light would become a central part of the Royal Commission.

The Commission’s Mission:

- To consider whether the private manufacture of and trade in arms should be banned, and whether the state should be the only body to make and sell arms. The Commission would also consider whether the UK should do this alone, or in conjunction with other countries.

- To consider whether what the League of Nations Covenant Article 8 (Section 5) described as the evils of the arms trade could be prevented.

- To examine present controls on the export trade in arms in the UK, to report whether these arrangements require revision, and if so how.

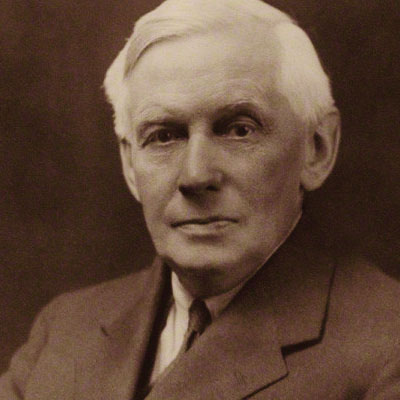

Above: A selection of those who testified against the arms trade.

From left to right: Christopher Addison, David Lloyd George and Dame Rachel Crowdy. All images © National Portrait Gallery, Creative Commons Licence.

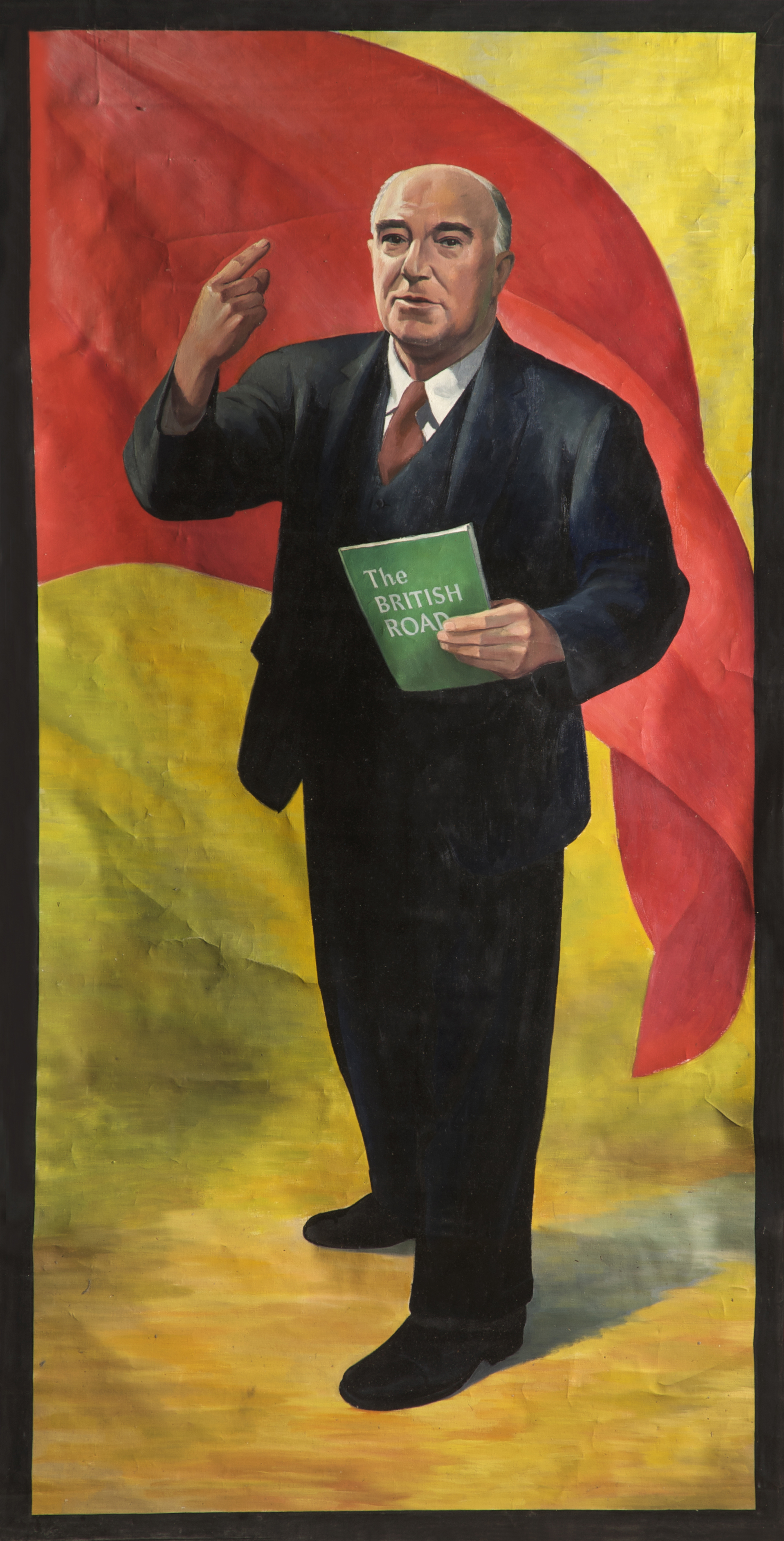

From the enormous weight of material sent in to the Commission just a few witnesses were selected. They ranged from Conservative Cabinet Minister (and League of Nations Union President) Lord Robert Cecil, war time Prime Minister and the creator of the Ministry of Munitions, David Lloyd George and his successor at the Ministry Dr Christopher Addison, to Communist leader Harry Pollit and radical MP Fenner Brockway.

In general, the witnesses for the prosecution made the common sense argument that arms manufacturers were likely to foment war and destroy peace by creating war scares in order to sell more arms, especially in international markets. Another line of argument was that private manufacture was less reliable than a state monopoly would be.

Harry Pollitt spoke for the Communist Party, using a wealth of statistical data to back up his argument. His figures, mostly from the League of Nations, showed that Britain was the largest global contributor to the international arms trade. He also revealed which ‘capitalists’ sat on arms firms’ boards. Those he named, controversially, included the Chairman of the Royal Commission, Sir John Eldon Bankes.

David Lloyd George and Christopher Addison had both held the position of Minister of Munitions during the First World War. Both appeared and gave evidence calling for a state monopoly of arms production and sale. Lloyd George said that re-arming doubles the holding values of a company, whereas disarmament halves them. He argued that profiting from the sale of arms was immoral and called, energetically, for nationalisation of the arms trade.

Christopher Addison had taken over from Lloyd George as Minister of Munitions in 1916. His evidence was based on his experience of the economics of munitions manufacture during the First World War. He argued that private firms had been incapable of producing enough arms for the war, while once the Ministry of Munitions was created in 1915 to bring production under state control it rose sufficiently. Addison called for a Ministry of Supply to be established as a single arms manufacturer able to effectively meet the state’s needs.

Sir William Jowitt, who gave evidence for the Union for Democratic Control (UDC), had major concerns that aircraft, and also raw chemicals that could be used in explosives, were exempt from export licensing. The manufacture of armaments could then be completed overseas (for instance, guns were fitted onto ‘commercial’ aircraft after being exported.) This aberration, Jowitt argued, could be averted only through a blanket ban of arms exports.

Another UDC witness, McKinnon Wood had worked in research and development in the Royal Air Force between 1914 and 1934. He stated that designs began as trade secrets and this meant that there was no uniformity of design in the Air Ministry. He was convinced that private manufacturers sold designs to foreign governments. The private sector was more likely to be tempted to sell national trade secrets to opposing countries than the government would be.

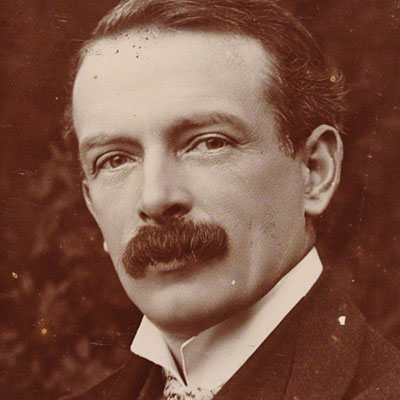

Above: A selection of those in support of the arms trade.

From left to right: Mr Charles Craven, Sir Herbert Lawrence, Sir John Eldon Bankes. All images © National Portrait Gallery, Creative Commons Licence.

I have no objection to selling to both sides. I am not a purist in these things.Harry McGowan, Chairman, ICI

The evidence against the ban on the private manufacture and trade in arms was given first by the directors of the arms companies, and then by the government departments who contracted the arms companies to produce arms.

Three representatives from Vickers gave evidence: the Chairman, Sir Herbert Lawrence, the Managing Director, Commander Charles Craven and the Director of Foreign Contracts, Mr F. Yapp. The Vickers representatives argued that their company had been maligned by the prosecution: in fact they made the most profit in peace time and were well controlled by the government, their main customer. Yapp controversially said that the prosecution held a ‘pacifist prejudice’: ‘an honourable but perhaps mistaken ideal respecting the sanctity of life’.

When the Chairman of Vickers, Herbert Lawrence was asked about this strange statement later he explained: ‘I think the sanctity of human life… has sometimes been exaggerated altogether to the disadvantage of certain other features of human life.’

Managing Director Charles Craven made the headlines when he clashed with Commissioner Gibbs. Craven claimed that Vickers products were no more dangerous than any other kind. He flippantly gave an example: he had never been injured by a gun, but once nearly lost an eye with a Christmas cracker.

Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) Chairman Harry McGowan was asked about their investments and shareholdings abroad. During the Chaco War between Paraguay and Bolivia ICI had supplied arms to Paraguay, while Vickers sold to Bolivia. McGowan was questioned whether this constituted an arms ring, which he did not deny. He freely admitted to combative Commissioner Gibbs that ICI sold chemicals to both Japan and China during their protracted conflict. After Gibbs asked for his opinion he said, ‘I have no objection to selling to both sides. I am not a purist in these things.’

John Ball from Soley Armaments Company, had caused a press sensation during the Nye Committee and was reluctant to appear again in London. Ball was the only arms dealer contracted by the British government to sell surplus small arms, although he also sold them for private companies such as the Birmingham Small Arms Company, (read more about this here.) The American inquiry had exhibited controversial letters between Ball and A.J. Miranda, the CEO of the American Armament Corporation. In one such, Ball urged Miranda to buy rifles from him to sell to China. China bought 100,000 Mauser rifles from the US government between 1931 and 1932, while the British had supplied Japan.

Soley Armaments controlled enough small arms to potentially upset the balance of power amongst smaller world states. This was risky in South America, because Ball desired that Miranda broker all Latin American munitions deals for him, but he could not afford to contravene British government export laws with massive exports. He hoped to use this moral restraint as mitigating evidence when he was called to attend the Royal Commission, but his evidence nonetheless caused quite a stir, not least when he said that rather than causing war he was ‘intelligent[ly] anticipat[ing]’ it.

I took a much lighter view of the ‘scandals’ until I heard the evidence for the defence.Commissioner Spender

After hearing the evidence for the defence the Commissioners were much more convinced that ‘evils’ such as selling to both sides in conflicts, bending (or breaking) the rules around exports and who arms could be sold to, corruption and fermenting war scares were inherent to the industry. Commissioner Spender later wrote ‘I took a much lighter view of the ‘scandals’ until I heard the evidence for the defence’.

The Secretary of State of the Cabinet and of the Committee for Imperial Defence, Sir Maurice Hankey was a militarist who feared disarmament would threaten what he termed ‘national virility’. He loathed the ‘symptoms of degeneracy manifested in peacetime.’ In his position as Cabinet Secretary and Secretary to the Committee of Imperial Defence (CID) from 1912 to 1939, when the CID was wound up, he truculently railed against disarmament at Geneva and played a substantial role in the breakdown of the 1925 Geneva Protocol. At the 1932 to 1933 disarmament talks he secured a defeat of Viscount Cecil’s 1932 Treaty of Mutual Assistance. In the calamitous 1933 talks that stalled the League of Nations he set up a campaign to sustain the levels of all UK battleships and aircraft carriers.

Hankey was firmly opposed to the creation of a Ministry of Supply, and dedicated much time and resources to preparing his department for their turn before the Commission.

In March 1936 two events took place which disrupted the hearing of the government’s evidence: Hitler moved troops into the Rhineland and the government’s second defence White Paper was published, showing a clear move towards rearmament.

The Commission was delayed and it wasn’t until May 1936 that the defence department’s evidence continued.

In his evidence, Hankey justified exporting arms to belligerent countries, curiously citing the scandal of Turkish troops munitions sold by British firms against British troops in the Dardanelles (read more about this here.) According to Hankey, it was an advantage to sell arms to your enemies as that way you would understand the weapons later used against you. Hankey would not admit any of the abuses which had been documented by the Commission. Influenced by his insistence that to do so would harm national security, the Commission stopped short of recommending the nationalisation of arms manufacture. They did, however, call for what Hankey dreaded almost as much: a Ministry of Supply.

The government was not pleased when the Commission recommended a Ministry of Supply, as this was an implicit critique of their rearmament strategy. The Commission’s report was presented to the Cabinet by Sir John Simon, and was then given to Hankey himself to make a decision on what do with it. Unsurprisingly, he did not leap to implement the recommendations he opposed and did nothing with it for three months. On 2nd February 1937 Hankey presented the Cabinet with an approved report, which omitted to mention any of the recommendations that contradicted existing government policy. On 6th May 1937 an almost verbatim copy of Hankey’s report was published as a white paper and acclaimed by The Times as a decision which would command the respect of ‘all men of common sense and moderation’.

The recommendation to create a Ministry of Supply would be realised only in May 1939; too late to really help rearmament efforts. The government had ignored the two million people who had sent evidence to the Commission, as well as establishment figures such as Christopher Addison and David Lloyd George, who had argued that state control of armaments production would provide a more effective defence. That the Commission took place at all is indicative of the strength of feeling against the private trade in arms at the time. Similarly to the Peace Ballot that took place the year before it is little remembered today, perhaps because of its proximity to the outbreak of the next world war.

The arms trade continues to enjoy an excessive influence over the Government. This has led to several official inquiries into the behaviour of arms companies either being stopped, stitched-up, or kicked into the long grass.

In 2004, following compelling evidence in the media, the UK’s Serious Fraud Office began investigating arms company BAE’s deals with numerous countries including Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Tanzania and the Czech Republic. However, the most important Saudi investigation was stopped in 2006 following political intervention by then Prime Minister Tony Blair. This was the result of pressure from the Saudi government and BAE.

In the US, a Department of Justice investigation continued. In 2010, the Department of Justice agreed a plea bargain with BAE. The company was sentenced to pay a $400 million criminal fine, one of the largest in the DOJ’s history.

The fine covered corruption on arms deals with Saudi Arabia, the Czech Republic and Hungary, although BAE only had to admit to making false statements in regulatory filings.

The longer-run UK Serious Fraud Office investigation was left with, as Private Eye put it, ‘the crumbs of a £30m settlement over BAE’s corrupt Tanzanian radar system contract.’ In this instance, BAE only had to admit to false accounting.

More information on the investigations and plea bargains is available here. Links to a number of the key legal documents are available here.

In November 2013 the UK Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee held an investigation into relations between the UK, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain. However, the report whitewashed the UK Government’s continuing support of the authoritarian regimes in these two countries, not least through arms sales. The prospects for an objective inquiry were scuppered when Sir William Patey, a former UK Ambassador to Saudi Arabia was appointed as a Specialist Advisor to the committee.

The BAE Annual General Meeting (AGM) has long provided a focus for anti-arms and anti-corruption campaigners, who have used the forum to focus on the activities and dealings of the company, in particular its alleged corruption in Saudi Arabia, South Africa and other countries.

On 5 May 2010 supporters of Campaign Against Arms Trade (CAAT) organized a ‘People’s Jury’ outside BAE AGM, featuring dozens of judges and a giant puppet of BAE Chairman, Dick Olver.

Evidence was heard from the crowd on charges including:

- Corruption

- Selling weapons to repressive regimes

- Targeting students and influencing university research agendas

- Undermining South Africa’s democracy

- Misleading the public about its commitment to British jobs

When asked for their decision, the People’ Jury was unanimous: GUILTY!

Meanwhile, CAAT supporters pursued the shorter and more lifelike version of Dick Olver inside with relentless and detailed questions on corruption. Olver’s response was comically shallow and scripted: repeating several times that BAE would “self-report” anything dodgy they found out about or knew. Andrew Feinstein (former ANC MP) called for him to resign on this issue.

Other comedy moments came when Olver described how BAE are “doing our bit” for the environment: limiting their number of corporate jets to one and profiting from a couple of small renewables spin-offs from their military work.

In September 2013 a group of activists was arrested for seeking to disrupt the setting up of DSEi (‘Defence Security Equipment International’) the world’s largest arms fair, held every two years in London. It exists so that arms buyers and sellers can come together, network and make deals. Activists blocked entrances to the venue by locking on together with arm tubes, by blockading a lorry and by holding space on the road with their bodies. They were charged various obstruction offences.

Following their arrests Caroline Lucas MP identified that two companies – Tianjin MyWay International and Magforce International – had illegally exhibited torture weapons at DSEi. These included weighted fetters, electronic stun guns and stun batons. A report by Amnesty International found that the weapons could be used for crimes against humanity – torture.

The trial groups demanded disclosure of information as to if and why the state did not investigate illegal torture weapons at DSEI. In the face of these continual requests, the cases were dropped a week before trial.

In March 2014 the protesters begun private prosecution proceedings against the companies that exhibited at DSEI. However, a meeting between the activists’ lawyers and the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) made clear that the prosecution could not be continued, despite refused freedom of information requests to HMRC and the Metropolitan Police about the investigations into breaches of the law at DSEI.

The CPS chose to communicate their position outside of the six month deadline for any public prosecution to be commenced. Legal representatives had repeatedly requested from the outset that the CPS commence their own proceedings against the two arms companies.

The activists commented:

‘We are appalled that the case has been discontinued. However, it proves our point – the commercial trade of arms, which causes unimaginable human suffering and tends to devastate the natural environment too, is legitimised, facilitated and rewarded by the authorities and our Government.’