/

/

Pankhurst’s newspaper Woman’s Dreadnought (later changed to Workers’ Dreadnought) pushed for improved pay and working conditions in munitions factories throughout the First World War. Her parliamentary observer heard reports of munitionettes at Armstrong Whitworth’s Elswick factory being forced to work shifts of twelve hours or more, and 95-hour weeks. Pankhurst campaigned unsuccessfully for their working day to be divided into three eight-hour shifts instead of two twelve-hour shifts, so that they would be less exhausted, and so that more women could be employed. She said: ‘Some were fainting from too much work, whilst others starved for lack of it.’

Women were working under appalling conditions, sometimes even dying from the dangerous fumes. The TNT used in shells was highly toxic, often causing liver damage. One of the symptoms of poisoning was jaundice, which turned the women’s skin yellow, so they were nicknamed ‘canaries.’

The women appealed to Pankhurst for help in improving their conditions, so she published the facts about their long hours and low wages. As a result, she received a solicitor’s letter threatening the ‘proprietors and printers’ of the Woman’s Dreadnought with libel action. Pankhurst regarded it as ‘an attempt to stifle criticism and an attempt to prevent exposure of injurious conditions.’ She appealed to readers to subscribe to a special fund to raise funds to fight the case.

Pankhurst did not oppose women working in munitions factories per se. She was pragmatic, realising that many women had lost their jobs when civilian industries contracted at the outbreak of war or were desperate to escape arduous and low-paid work in domestic service. But she pointed out repeatedly that while the munitions firms were making substantial profits, the workers’ wages lagged far behind the rising costs of living. The government made a promise to limit the profits of private munitions manufacturers, but Pankhurst said it was ‘a sop – a sham.’

In the Dreadnought, Pankhurst drew attention fearlessly to the harassment faced by people who opposed to the war. She declaimed corruption and profiteering. Despite constant vilification in the press, she continued to organise meetings and demonstrations, and to print articles about activists from around the world. She did all this despite oppressive surveillance of her activities by the authorities, and with apparent disregard for the personal consequences.

These were unpopular causes when every family had a man at the front, and Pankhurst was accused of treason by political leaders, and even by her own mother, Emmeline, who was actively in favour of the war. Pankhurst was herself banned from travelling abroad, even to the First International Women’s Peace Conference (1915) which she had helped organise, while Emmeline trotted the globe freely, banging her imperialist drum.

After the war, in 1920, Pankhurst was accused of ‘unlawfully publish[ing] ideas likely to cause sedition and disaffection among H.M. Forces.’ She was a leading light of the Hands Off Russia! campaign, and the offending article urged Dockers not to load ships supplying arms to anti-Communist forces, just a few months after the successful boycott of SS Jolly George. It was called The Yellow Peril and the Dockers by a Jamaican journalist called McKay, who wrote under the pseudonym ‘Leon Lopez.’ Pankhurst refused to name the author, or divulge the source of his information, and was jailed under severe conditions for six months in 1921 for this act of defiance.

Pankhurst did much humanitarian work in the East End of London during the war. There were endless cases of babies dying of starvation, and elderly widows, unable to live on the five shillings pension a week, threatened with the dreaded workhouse. Within two weeks of the declaration of war, Pankhurst opened a cut price restaurant, which served 400 meals daily, for a penny a meal. She established a free clinic for babies, providing medical care and distributing milk, eggs and clothes. She turned a disused pub, ironically called The Gunmaker’s Arms, into a nursery, called The Mother’s Arms, which she ran on Montessori lines.

In her autobiography, The Home Front, Pankhurst describes the toy factory she opened in 1914 Bow. It employed 59 women, who were paid the equivalent of what was then the man’s minimum wage – £1 per week. There is little evidence to prove she was trying to provide an alternative to munitions work. But she saw the toy factory as a means of offering working class women creative and fairly paid work – a contrast to many arms companies. (Pankhurst was herself a gifted artist who had turned her Royal College training to poster design for the ‘Votes for Women’ cause).

There was a market for toys in London, as German imports had stopped, and some businesses providing home-produced goods were thriving. Pankhurst engaged two art students from Chelsea College as designers. They encouraged the women to create their own designs, ‘and if any of them produced a toy which was saleable, the factory purchased it and paid royalty on the sales.’ She took the toys to Selfridges and persuaded the owner to stock them. The factory also offered singing classes and French lessons to the workers.

Pankhurst was as fearless in this venture as in all her others. She employed a German woodworker, who had lost his job at a wood yard, because his employers were afraid ‘jingo-patriots’ would attack them. He had seven children to support, and she paid him the same wage he had been getting in the wood yard. She also engaged a Polish woman as manager.

She did not try to make political capital out of the war, but saw her role as ‘to make things better for those who are suffering because of the war.’ In that she was certainly successful.

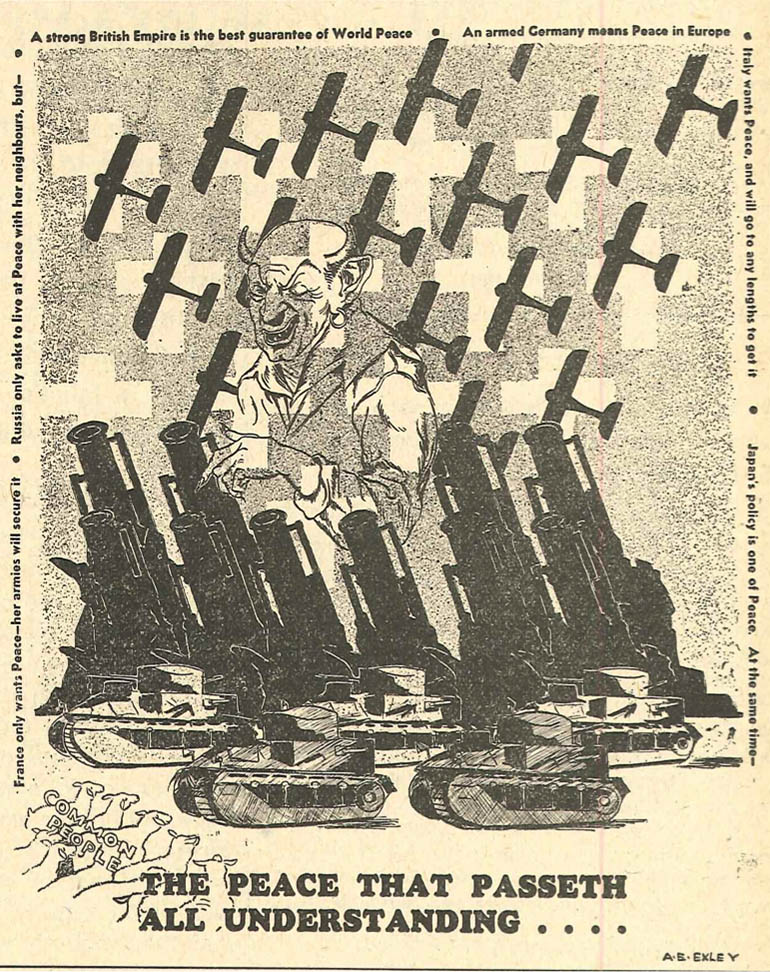

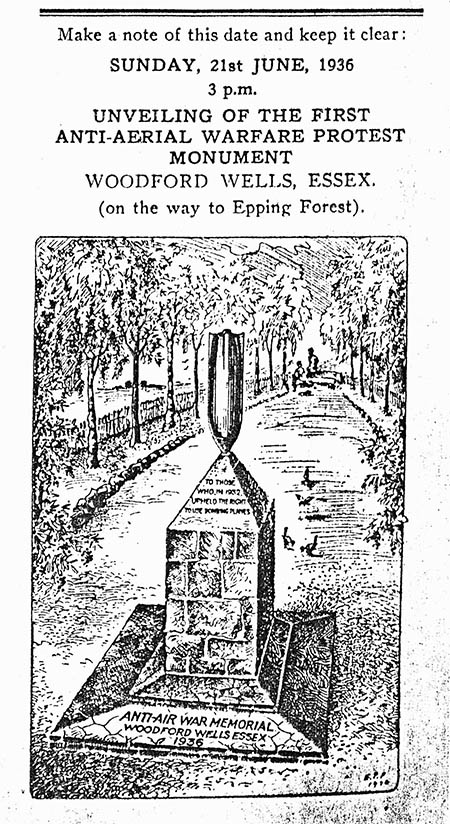

In 1932, politicians gathered in Geneva for the World Disarmament Conference. Amongst other subjects, they debated air warfare, but to Pankhurst’s dismay, failed to ban it. By this time, Pankhurst had moved to Woodford Green, and was living frugally with her Italian lover, Sylvio Corio, and their son Richard, in The Red Cottage.

Pankhurst had witnessed the first Zeppelin raids on London during the First World War, and when she heard the news from Geneva, she commissioned an anti-air warfare monument by the sculptor Eric Benfield. Its plinth is in the form of a pyramid, on which a stone bomb has landed as if it had just fallen from the sky. ‘To those who in 1932, upheld the right to use bombing aeroplanes, this monument is raised as a protest against war in the air;’ her inscription was a j’accuse. The New Times and Ethiopia News exclaimed, ‘There are thousands of memorials in every town and village to the dead, but not one as a reminder of the danger of future wars. The people who care for Peace in all countries must unite to force their Governments to outlaw the air bomb. We must not tolerate this cruelty, the horror of mangled bodies, entrails protruding, heads, arms, legs blown off, faces half gone, blood and human remains desecrating the soil.’

Unveiled on 20th October 1935, the monument was smeared with creosote by fascist sympathisers on its first night, and stolen soon afterwards.

But Pankhurst was not to be defeated. Eric Benfield made a replacement. The publicity caused by the theft ensured that when it was unveiled again on 21st June 1936, it attracted great interest, with representatives coming from Germany, France and Austria, as well as Ethiopia. It is still there today, although The Red Cottage has since been demolished. As W H Auden said, it is ‘one of those ironic points of light, that flash out wherever the just exchange their messages.’

East London, which saw some of the worst bombing in the Second World War during the Blitz, now plays a major role in fuelling weapons sales around the world. Every two years since 2001, the ExCel exhibition centre has hosted ‘DSEi’, one of the world’s largest weapons fairs.

The most recent East London arms fair in 2013 was visited by 30,000 arms buyers and sellers. Militaries and police forces from Bahrain, Colombia, and Turkey – each engaged in brutal suppression of unarmed protesters – browsed for more weapons. The main weapons suppliers to Syria’s President Assad in the brutal and ongoing civil war were also there.

But vast sums of public money being spent on fuelling conflict and human rights abuses was not the only story that week. The arms fair was challenged with daily creative direct action which impeded its business. Grim reapers blockaded an exclusive arms dealers’ dinner at the iconic Cutty Sark; cheeky protesters ‘helped’ arms dealers arriving at the airport by sending them cheerfully off in the wrong direction. Watch the video, read more and take a look at the media coverage from the week.

Over the years, ordinary people have found lots of other impressive ways to undermine and expose the devastating business that takes place at the arms fair: in 2011, five kayaks blockaded a warship headed for the docks at the ExCel centre, in 2007, the Space Hijackers managed to raise enough money to buy a tank and drive it on the arms fair. 2003 saw activists buy an exhibition space for the ‘Affinity group‘ PR firm, before revealing a banner on the roof of an armoured vehicle!

Find out more and get involved:

East London Against Arms Fairs – www.elaaf.org

Stop the Arms Fair – www.stopthearmsfair.org.uk