Although the new factories were government property, they would be designed, constructed and managed by local business people subcontracting to an established armaments company. The established armaments firms wanted the new heavy shell factories to be run as if they were an ‘extension to their existing works.’

Just three days into his job as the new Minister of Munitions, Lloyd George visited Bristol and met with a local group of eminent businessmen – including several railway directors – who formed the West of England Munitions Committee. This meeting resulted in schemes for a national shell factory in Bristol that would produce empty shell casings and a national shelling filling factory in Quedgeley, Gloucestershire. The urgency of total war meant factories sprang up in anywhere and everywhere; railway workshops, textile mills or, in the case of Quedgeley Ammunition, a farm requisitioned under the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) from one Curtis-Hayward, whose hedges and ditches were completely destroyed.

Increased storage capacity was needed for explosives and propellants (some of which were imported from the USA). In October 1915, the Berkeley Estate in nearby Slimbridge – a relatively isolated area – was chosen as one of the country’s two largest storage magazines for the propellants. In December 1915, notice ‘was served on nine estate tenants, Lord FitzHardinge; Earl of Berkeley and George Tudor under DORA. Until 1918 ‘much financial hardship was endured by the tenants’ due to the loss of access to their land. In April the value of the work was £137,000 and by July when the factory site was complete it had reached approximately £200,000.

Even though 70 of the women first employed at Quedgeley were given training at Woolwich (the rest were trained on site locally), the shell and cartridge filling work was considered unskilled. The only requirement was a steady hand and readiness for work. Quedgeley transformed the labour market in nearby towns. The majority of women workers came from domestic service, which was commented upon in a local newspaper, ‘It has been deemed unpatriotic to employ men servants who could serve their country in the war, and now we are told that the demand for woman’s work in munitions and other factories is so urgent, that the retention in private houses of women servants who could be dispensed with, is a crime against community… How to get through the complicated work of a large household with less help, will be a serious question for numbers of housewives.’

Approximately 20 percent of the workforce consisted of young men less than 18-years old, men considered too old for military service, and wounded or discharged soldiers; this demographic remained for the duration of the factory’s operation.

| Date | Women | Men | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| June 1916 | 2,113 | 307 | 2,420 |

| September 1916 | Unknown | Unknown | 3,916 |

| December 1916 | Unknown | Unknown | 3,212 |

| March 1917 | Unknown | Unknown | 6,364 |

| October 1917 | Unknown | Unknown | 4,459 |

| January 1918 | Unknown | Unknown | 4,664 |

| October 1918 | 5,070 | 1,157 | 6,227 |

Table 1. Workforce in the National Filling Factory at Quedgeley

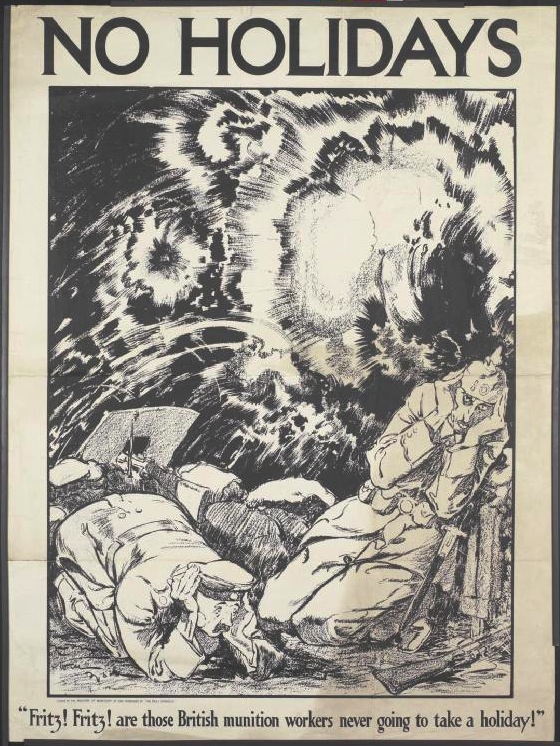

'Fritz! Fritz! are those British munition workers never going to take a holiday!'/© IWM (Art.IWM PST 13307)

'Fritz! Fritz! are those British munition workers never going to take a holiday!'/© IWM (Art.IWM PST 13307)The factory site was divided into danger and non-danger areas, the latter housed changing rooms and other facilities while the former contained workshops and storage magazines. Filling shells could result in toxic jaundice due to TNT poisoning and yellowed skin, hence munitionettes were nicknamed ‘canaries.’ We do not know precisely how many women died from this condition, nor are there recorded numbers for Quedgeley.

When the factory began operations, not all of the workshops and magazines were ready for use but due to the urgent requirement for ammunition the Ministry of Munitions encouraged the use of any available building. This increased the hazardous conditions for the workers, with explosives stored in bulk next to workshops and large shell filling carried out in small fuse stores. A safety official visited the factory in June 1916; he found a considerable quantity of breach-loading shells and incomplete 18 pounder quick-firing ammunition in areas intended for empty shell storage. He recorded 26 girls filling large 60-pound shells with 100 pound loads of gunpowder in the store, contrary to regulations. As a temporary solution the factory reduced the gunpowder load to ‘not more than 25lbs at any one time!’

Those employed in the danger areas were issued flannel overalls; white was given to the TNT workers. These overalls included a coat, cap and trousers without turn-ups or pockets, but offered no special protection and were not fireproofed, even though that had been the original intention.

As production got underway, workers were prevented from taking holidays because the first Easter had resulted in a fall in output, hence all national holidays throughout the rest of spring and summer were postponed. In September 1916 a four-day rest period was allowed. In 1918, Winston Churchill, the new Minister of Munitions, made an appeal to the workers to continue output during that last Easter period.

Upon the declaration of peace – 11th November 1918 – all workers were given three days holiday with pay. They then returned to stock stake and clean the factory, and by the end of November 1918, 75 percent had been dismissed.

It was intended that production would reach 40,000 rounds of quick-firing ammunition and 250 tons of breech-loading cartridges per week, but factory output exceeded all expectations. The Ministry of Munitions documentation contains a record of a telegram sent to Quedgeley at the end of the war: ‘The Controller and Directors of the Gun Ammunition Filling Department desire to express their great appreciation of the part played by the staff and workers at National Filling Factory No.5 Quedgeley, in achieving such a glorious victory.’

National Filling Factory No.5 Summary of Output

This table was originally recorded in MUN 5/365/1122/50, The National Archives

| Type | Amount |

|---|---|

| 18 pounder shell filled with block charges | 10,279,557 |

| 4.5 inch shell filled with block charges | 384,269 |

| 60 pounder shrapnel shell filled | 17,400 |

| 2.75in, 4.5in, 6in, 8in, & 9.2inch cartridges filled | 7,005,746 |

| Trotyl (TNT) exploder bags & cartons filled | 8,489,084 |

| Fuses Nos. 100, 101, 102 & 103 assembled | 2,511,275 |

| Fuse no. 106 assembled | 566,887 |

| CE pellets compressed for fuse 106 | 106 502,996 |

| Primers filled | 11,501,459 |

| value-1 | value-2 |

Table 2. Summary of Output National Filling Factory No.5 from 13th March 1916 – 21st November 1918

Archived – A Poem Inspired by Research into Quedgeley by Michelle Thomasson, 21st March 2014

Keep Calm

and have an ordinary day,

boxed files with history

are waiting to meet us.

Yellowing papers

carefully catalogued

into a silence.

Do Not Disturb

the collection’s sleeping conscience.

Leaders chosen,

most carefully selected,

to win at all costs

and profit.

Keep the home fires burning,

it’s alright it’s a job

maim and destruction

shilling a week, yes, just a bob.

You see,

the most intellectual, honorary gentlemen

have devised

Royal Society chemical recipes to burn out their eyes.

It’s alright it’s a job,

TNT into shells without any protection,

that costs too much mate,

while the men on the front

cost nothing at all,

they’ll only last for four minutes,

in blood, guts and squall,

most terribly inconvenient

a rifle shortage for a huntsman’s ball.

Returning documents to archive,

they have to be weighed

just a few grams evaporating,

that’s OK,

but everything else must stay the same.

The economy of despots and madness,

still remains,

our heritage, our history

written and shelved

quiet

the pain.

Please dismiss any attempt

at researcher’s remorse,

comments will be moderated

and later stored,

archived as sanity

feelings ignored.

These words are too heavy,

please take them away.

Keep calm,

and I hope

you have a most unusual day.