The movement included members of the Independent Labour Party, the British Socialist Party, Workers Socialist Federation, and the Herald League, who wanted to show international workers’ solidarity with their Russian comrades. Where other attempts at cross-factional unity had failed, the Hands Off Russia! campaign proved to be a powerful galvaniser of British left-wing sympathisers. It really got going in January 1919 when a National Committee for the Hands off Russia! campaign was elected at a conference in London. Many of the groups and individuals who congregated under the umbrella of Hands Off Russia! later went on to form the Communist Party of Great Britain in August 1920.

In 1919, 2.4 million workers went on strike, after weathering four years without trade union rights. Both the Labour Party and official trade unions had accepted the Munitions Act of 1915; ‘a system that was military-like in its restrictions and enforcement’. It made strikes illegal, controlled wages and made it impossible to leave a job without permission. Union membership grew during the war years, when the labour system was seen as undemocratic and damaging to working class interests. Then in 1919 and 1920, as Lloyd George’s promise of a land fit for heroes failed to materialise, industrial unrest grew. Those industries still largely under government control such as mining and railways were especially militant, while workers on Red Clydeside fought for a 40-hour week. (Read more about Red Clydeside here).

In this context, Hands Off Russia! began to gain support amongst the rank and file in 1920. Workers were troubled by the prospect of another imperial intervention, and the possible extension of unjust policies disguised as emergency war measures.

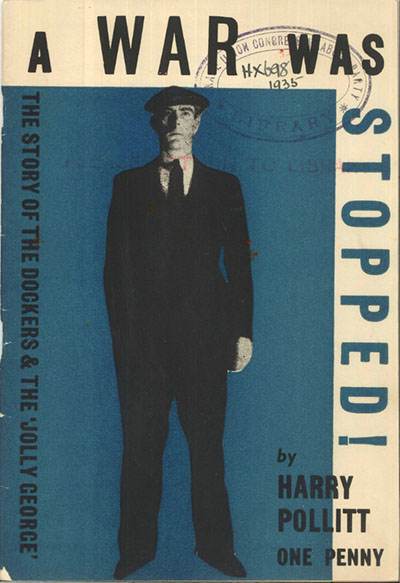

The coal heavers have refused to coal the SS Jolly George on May 10th 1920. They struck better than they knew!…The strike on the SS Jolly George has given a new inspiration to the whole working class movement. On May 15th, the munitions are unloaded back onto the dock side, and on the side of one case is a very familiar sticky-back, ‘Hands Off Russia!’ It is very small, but that day it was big enough to be read all over the world.

Harry Pollitt, 1935

The London Dockers’ boycott of the SS Jolly George was the most tangible success of Hands Off Russia! – a campaign that had held meetings and demonstrations for many months. In May 1920, dock workers refused to load this ship with British armaments bound for Poland to be used by Russia’s anti-Bolshevik White Armies. They resisted orders, and significantly, the District Secretary of the official Dockers’ Union, led by Fred Thompson, backed their action.

The Dockers’ refusal to load the SS Jolly George with weapons destined for the White Terror was a powerful show of solidarity, but their radicalisation did not happen overnight. Along with Harry Pollitt, Sylvia Pankhurst was instrumental in preparing the groundwork. Pankhurst was a prominent communist and led the Workers’ Socialist Federation of which Pollitt was a member. In the months before the SS Jolly George incident they undertook a campaign of relentless agitation: handing out pro-soviet literature, making links with unions, and radicalising the dock workers. Pankhurst reportedly handed out thousands of copies of Lenin’s Appeal to the Toiling Masses around the docklands for several months beforehand, at the risk of arrest, as the text was on the Home Office blacklist. A year later, in 1921, Pankhurst was arrested and imprisoned for stirring up anti-establishment feeling amongst the Dockers.

In his autobiography Serving My Time, Pollitt also credits the propaganda of an unsung figure: Mrs. Walker of Poplar. ‘She toiled like a Trojan. If on a shopping morning you went down Chrisp Street, Poplar, you could rely upon seeing Mrs. Walker talking to groups of women, telling them about Russia, how we must help them, and asking them to tell their husbands to keep their eyes skinned to see that no munitions went to help those who were trying to crush the Russian Revolution.’

The SS Jolly George incident united anti-war, anti-arms and anti-capitalist agitation in a common goal, for a moment a least. This was in part due to the timing of events. Anti-war and anti-arms sentiment was much more prevalent amongst the rank and file workers following the devastation of the First World War. The Dockers were not necessarily committed Bolsheviks; it was the threat of another war ‘of imperialist plunder,’ and its consequences for labour, that convinced them to strike. Churchill was eventually put off armed intervention by the hostility of the workers. ‘Defence of White Russia began to be identified with defence of the trade unions against Lloyd George.’ Although it was highly unlikely that any allied intervention in Russia would have led to a full scale war, Pollitt really believed they had stopped a war, and so did many of his rank and file supporters. This illustrates the state of fear and mistrust of British military decision making at the time.

In the North

The armament firms have much akin to commercial travellers whose favourite method of coercing orders is to work their victims ‘on the cross.William Paul

Even the Home Office reluctantly admitted that, ‘there were remarkable demonstrations against the war [of intervention in Russia] in practically every part of the country’. This widespread agitation led to the formation of a Council of Action of the Trades Union Congress and the Labour Party, in August 1920. The campaign was not just a fringe group of dissident workers and agitators but a union-backed, countrywide movement. While leaders may have been staunchly communist, fighting to help their comrades in Russia, the rank and file were largely disillusioned workers who conflated the defence of Russia with the defence of workers’ rights at home.

William Paul was a Hands Off Russia! campaigner based largely in Derby and Manchester. He was involved in revolutionary activity throughout the north of England and used his expanding market stall business to move around the region, connecting radical thinkers and distributing literature. He ran for MP in Rusholme, Manchester in 1923 and 1924, was at various times editor of The Socialist, the Communist Review, and later The Sunday Worker. Paul spoke at several prominent Hands Off Russia! demonstrations, particularly in Manchester. He wrote extensively about the atrocities of the First World War, the exploited workers who were forced to bear the brunt of it, and the callousness of the arms trade.

‘The armament firms have much akin to commercial travellers whose favourite method of coercing orders is to work their victims ‘on the cross.’ Thus, an armament firm shows that a certain country must arm itself against some other nation. Should the first nation give an order, the firm at once warns the second nation that the first one is arming against it!…Thus at one time Argentina and Chile had cruisers building alongside each other at Armstrongs in anticipation of having a scrap at each another!’

Four years of war has seen the toiling millions of the industrial world forced and hounded by senile laws to expend their labour upon transforming billions of pounds worth of wealth into millions of death-dealing instruments of human murder.William Paul

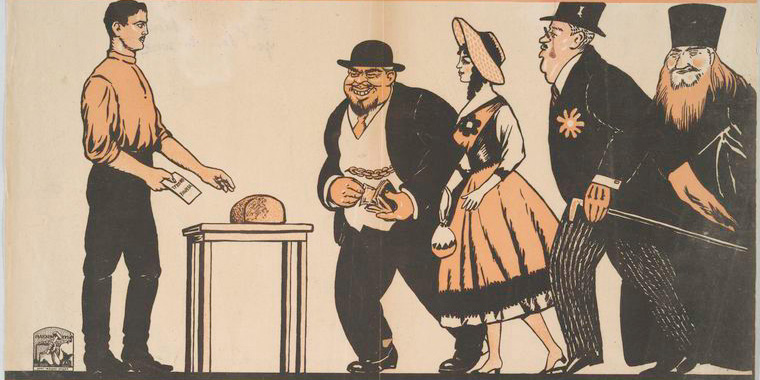

Labour is bread - Who doesn't work doesn't eat, 1917-1921 / Creative Commons

Labour is bread - Who doesn't work doesn't eat, 1917-1921 / Creative Commons

The literature and rhetoric of the Hands Off Russia! Campaign, like that of John Maclean and other contemporary left-wingers, effectively used the armaments industry as a powerful metaphor for capitalism.

The idea of ‘profits before people’ came up again and again. Capitalism allowed private arms companies to profit from a national crisis. During the war the industrialists grew fat on slaughter, while at home workers were forced to work longer hours in dangerous conditions. The Munitions Act, sanctioned by the established left, prevented workers taking advantage of the law of supply to demand an increase in wages as living costs soared. Workers could only withhold their labour on pain of arrest and deportation, which stymied the Clyde Workers’ Committee leaders in 1916. Hands Off Russia! roused anti-capitalist sentiment in order to obstruct another conflict intended to destroy socialism abroad.

The army and police rely on tear gas, bullets and weapons from abroad … We ask you to take action … Shut down the arms dealers. Do not let them make it, ship it.

A call from Tahrir Square, 22 November 2011

Egypt: Dockers’ Resistance

In November 2011, Egypt’s security forces launched brutal attacks on protesters in Tahrir Square and across Egypt. The popular uprising of February 2011 had overthrown authoritarian leader Hosni Mubarak, only for him to be replaced by military rule, responsible for ‘even worse’ abuses.

Huge quantities of teargas were used in the November attacks. Characterised as a ‘less lethal’ weapon, designed for ‘crowd control’, teargas was here used to lethal effect against civilians to suppress calls for democracy. Thousands were injured in the suppression and dozens died.

Just as London’s dockworkers had interrupted the supply of weapons to Russia in 1920, Egypt’s Dockers in 2011 also took action to protect the revolutionaries, with customs employees refusing “one after the other” to sign to allow a new 7 ton shipment – travelling from the US port of Wilmington, aboard the Danish ship Marianne Danica – to enter the port in Suez.

Bahrain: Stop the Shipment

Protests at South Korean government buildings helped increase the pressure on the government to stop exports to Bahrain/

Protests at South Korean government buildings helped increase the pressure on the government to stop exports to Bahrain/In 2013, campaigners learned that South Korea had been asked to fulfil a massive order of over 1.6 million rounds of teargas – more canisters than there are people in Bahrain. An international campaign was quickly launched to stop the shipment. People from across the world used email and twitter to share stories of the impact of teargas in Bahrain with the Korean licensing authorities – and activists in the UK and South Korea took action at embassies and government buildings calling on South Korea to Stop The Shipment.

Just a few weeks later, DAPA, South Korea’s arms export licensing agency, confirmed that due to ‘political instability’ and pressure from international rights groups they would block the export. Shipment stopped!