WILPF used the disarmament petition – ‘one of the most important pieces of work’ they had undertaken – as an excuse to lobby government officials and sponsor demonstrations. The organisation (established in 1915) forwarded a plethora of signatures and letters to the World Disarmament Conference President Arthur Henderson. He replied, ‘I venture to express the hope that you and your friends who are in favour of success will not relax your efforts until it has brought its work to a successful conclusion’. Although WILPF proved that millions craved disarmament (in North Wales the response was particularly strong) there was concern that if delegates ‘should begin with the discussion of all sorts of technical details [about weapons] there would be no possibility of creating a much needed psychology of peace.’ Sadly, their fears were realised.

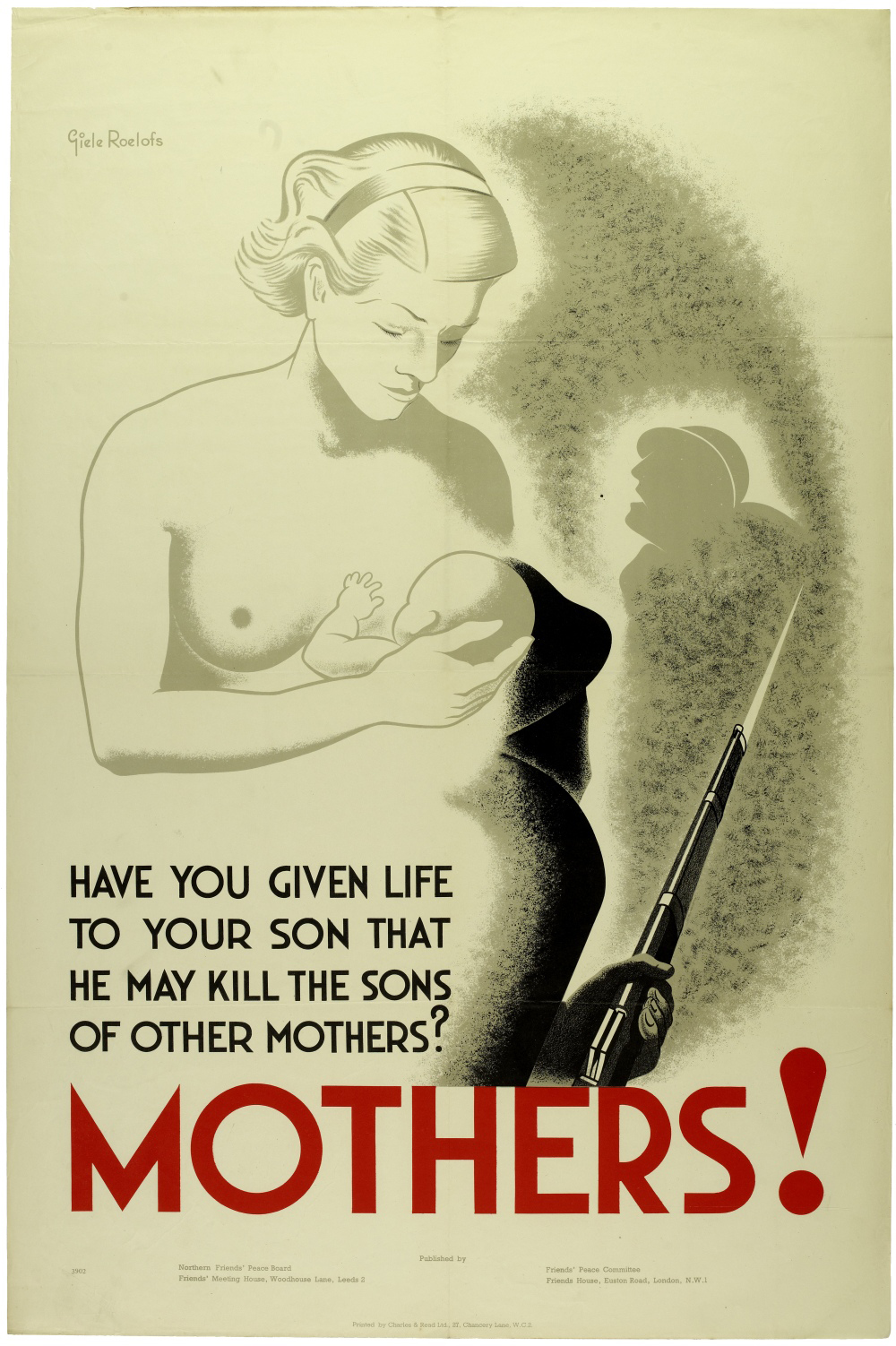

Mothers! Have you given life to your son that he may kill the sons of other mothers?/© Northern Peace League

Mothers! Have you given life to your son that he may kill the sons of other mothers?/© Northern Peace LeagueThe first phase of the World Disarmament Conference opened on 2nd February with delegates from 60 countries. Olga Miser of the Austrian section of WILPF commented, ‘I feel the delegates there treat us contemptuously.’ WILPF had lobbied heavily for a female delegate to be present at the conference; Mary Emma Woolley was chosen to represent and remain in direct contact with WILPF throughout. WILPF’s efforts were once again hampered by women’s inequality and lack of political influence in many nations.

The opening session was marred by conflicting national interests, especially the polarisation of France and Germany. The USA delegation called for the abolition of all offensive weapons as the basis for the negotiations. But France insisted security must precede disarmament and asked for an international police force to strengthen the League of Nations and for the implementation of an arbitration process.

The French plan was doomed when Germany, Britain, Japan and the USA all asserted that the League lacked authority to command an international force.

The Germans demanded equality as the basis for peace. They proposed a prohibition on the use and manufacture of chemical and bacteriological weapons, as well as the abolition of tanks, heavy artillery and conscription. Germany’s proposal for qualitative disarmament was not favourable towards France, but gained a favourable response from the USA and Britain.

Another stumbling block was that nobody could agree what constituted ‘offensive’ and what constituted ‘defensive’ weapons. This question, like at previous international negotiations, was diverted to a sub-committee for yet more fruitless discussion.

The conference at this point abandoned open sessions and productive discussion had stopped when the conference broke for Easter. WILPF’s fear of a deadlock was realised. Disarmament groups had grown disillusioned with the lack of progress and realised ‘that the present social, political and economic conditions of the world are the consequences of an outworn system.’

The lack of progress also caused internal strife within WILPF. Several WILPF members questioned the efforts and performance of Mary Woolley. She was accused of being afraid to antagonise delegates for disarmament concessions and for not making her feminist position known. Public statements from Woolley’s peers confirmed the belief ‘that her business was to antagonise and thus to establish women’s place on official commissions’. WILPF’s leading members were also conflicted on the arms reduction issue. Emily Greene Balch believed pursuing complete disarmament was unrealistic, whereas arms reduction was achievable. Both Dorothy Detzer and Hannah Hull believed only in universal disarmament and thought pursuing a policy of arms reduction made WILPF ineffective.

WILPF became convinced that as long as there is profit in war, the international trade in munitions would continue to flourish. ‘Women everywhere watch with horrors and fear the increasing of armaments, fully convinced that they cannot but lead to new wars’. In April 1932, the organisation began the process of obtaining a congressional investigation into the munitions industry in the USA, which came to fruition in the Nye Committee. This stimulated the British to investigate the private arms industry too.

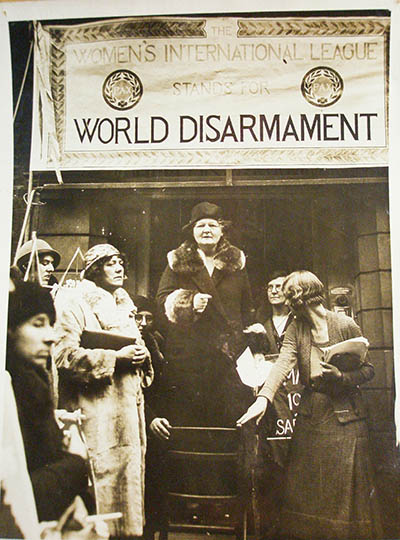

Women's disarmament campaigner c.1932/© Women's International League for Peace and Freedom/ © Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science, LSE/WILPF/22/1

Women's disarmament campaigner c.1932/© Women's International League for Peace and Freedom/ © Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science, LSE/WILPF/22/1WILPF alongside other pacifist groups, such as No More War Movement, created a transnational collaborative body called the International Consultative Group for Peace and Disarmament (ICG), in order to propound a unified line of policy. Under the ICG banner rallied ‘all the forces of peace, the communists, socialists, churches and pacifists against the militarists, governments and profiteers.’ Cooperation between disarmament groups stood in stark contrast to the behaviour of government delegates.

Adolf Hitler, Germany’s new Führer, opposed the disarmament plan presented by French President Edouard Herriot. Hitler refused to accept any reductions in armed forces and claimed that since Germany was already disarmed, the other countries should follow its lead. British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald offered a plan in March 1933 to reduce European armies by almost 500 thousand men, with France and Germany enjoying military equality.

The equality of rights for Germany was a major disappointment for WILPF as it threatened their vision of a new international order. While the USA supported MacDonald’s proposal, the plan collapsed when the Germans insisted that Storm Troopers should not be counted as soldiers!

The conference adjourned between June and October and during the interval desperate attempts were made to reach an agreement. In the final negotiations, Britain, France, Italy, and the USA offered not to increase their armaments for four years and at the end of that time Germany would be allowed to rearm to the same level as the other four powers. In response, the Germans demanded immediate equality in ‘defensive weapons.’

Melanie Vambery of WILPF’s Hungarian section lamented that ‘many international organisations are on the verge of annihilation.’ Monetary issues were very pressing for WILPF, which relied solely on public donations and charitable giving to stay at the conference.

WILPF staged a mass demonstration on 19th March and presented eight million signatures to Arthur Henderson. In April it ran a study conference on the obstacles to disarmament in Geneva in a desperate push to revive the conference. In the late summer of 1933, national branches of WILPF were told to press their respective governments and to support a six-point resolution advocating no rearmament, qualitative disarmament, budgetary limitation, strict supervision and a permanent supervisory organisation. A further demonstration was also scheduled for 15th October in Geneva with meetings and messages of support being sent to WILPF and other pacifist groups.

Despite the pacifist movement’s best efforts, on 14th October 1933 negotiations collapsed. The German foreign minister announced that he felt ‘compelled to leave.’ The World Disarmament Conference limped on until June the following year, but WILPF recognised all hopes for a peaceful political settlement in Europe were thwarted. Without German participation, the conference was meaningless.

Margaret Bonfield: WILPF member and Britain's first female cabinet minister/© Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (UK)

Margaret Bonfield: WILPF member and Britain's first female cabinet minister/© Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (UK)The collapse of the World Disarmament Conference was an unparalleled blow for WILPF and the peace movement. WILPF blamed negligent governments and a conference was convened to educate ‘public opinion…to understand the nature of the protest Germany had made’. A significant weight of expectation had been placed upon the conference and the growing climate of war had made organisation difficult, memberships drop and placed a significant economic burden upon WILPF.

The failure of 1932 did not end WILPF’s efforts to rein in the arms trade and end war. External pressures forced WILPF to re-evaluate and refocus their efforts, ushering in a new forward thinking generation. The diversity of members included men and more liberated women, who at one point even considered dropping ‘Women’s’ from their title. WILPF became increasingly less dependent on the older suffrage personalities and networks to forward the group. However, Jane Addams still promised ‘to defend those at the bottom of society who, irrespective of the victory or defeat of any army, are ever oppressed and overburdened’.

Read about the WILPF’s activism during the First World War.