Through the policy of war, expansion, and reckless Imperialism, the whole of that money (£400,000,000) had been thrown into the sea.Francis Channing

While the 1905 Finance Bill was being debated, Mr Thomas Buchanan, Liberal MP for Perthshire complained vigorously that Parliament was being kept in the dark over how much money would be spent on the military that year: ‘How was it possible for the House to consider the expenditure of the year unless they were supplied with this information? … The Chancellor of the Exchequer ought to be able to say within a couple of millions what the expenditure on the Army and Navy for the year would be. It was not treating the House fairly not to give that information. This process of delaying the details of expenditure had been going from bad to worse during the past ten years.’

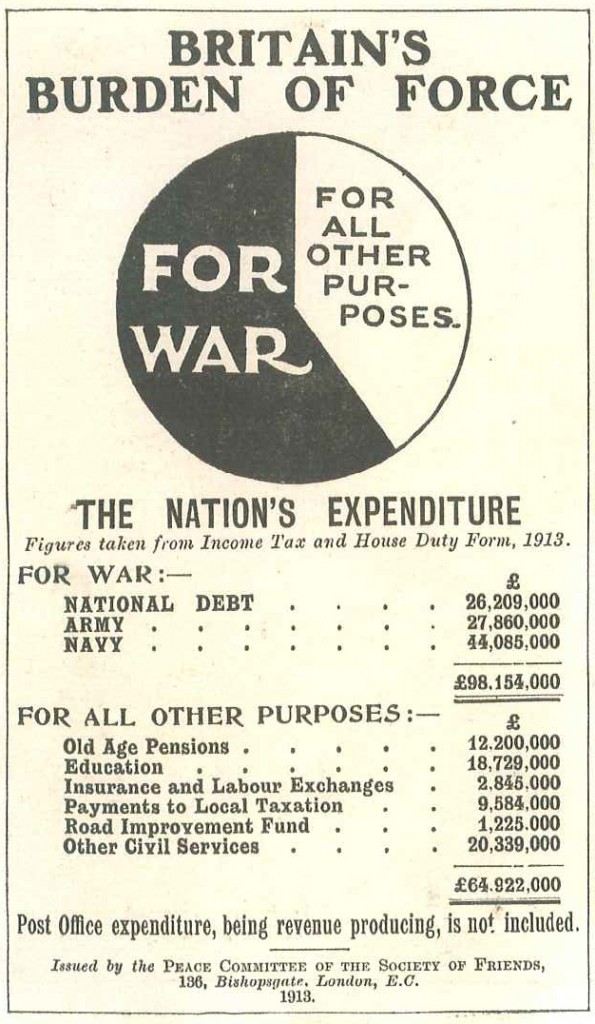

Northamptonshire MP Francis Channing argued: ‘Allowing for the repayment of capital charges for military and naval works, the total expenditure on war and armaments during the last ten years amounted to something like £400,000,000. Through the policy of war, expansion, and reckless Imperialism, the whole of that money had been thrown into the sea.’

‘Placed at 5 percent the mere interest on that sum would have provided universal old-age pensions for ever without any further appeal to the taxpayer.’

The Liberals would continue to debate military spending; in August 1905 they argued in the Naval Works Bill that spending on the Navy tended to escalate far beyond what was initially planned or promised in Parliament.

Ivor Guest, MP for Plymouth, pointed out that military spending was often wasteful as expensive equipment soon became obsolete: ‘It was a delusion to consider these naval and military works as of a permanent character. The world was littered with such works that had nothing but a slight archæological interest, and it was unfair to impose upon future generations the cost of works that might be considered useless, just as we considered much of the expenditure of our forefathers useless.’

Ivor Guest continued, ‘Nothing could be more temporary than military or naval works, and it was extremely impolitic and unfair to throw upon a future generation the obligation of paying for defensive or offensive works which would probably in a few years cease to be of any practical value either for military or naval purposes. Their descendants in the near future might come to the conclusion that the whole system of their naval strategy required revision.’

A major issue in the debate surrounding the 1905 Naval Works Bill was the large amount of borrowing proposed in order to cover the costs. The government planned to repay this money over 24 years, which was considered unfair to future generations. Despite ‘a unanimous expression of opinion against the system of borrowing for military and naval works’, the government seemed intent on spending on the army and navy, whether or not this increased public debt. An underlying question seemed to permeate the debate, why in times of peace was so much investment being channelled towards arms?

Francis Channing’s main point was that the result of government spending on defence is not only a lack of money for welfare, it also results in the unjust taxation of the poor

‘The additional expenditure … had been estimated to involve extra taxation to the extent of a penny per working day upon every man, woman, and child in the country. To the women employed in ‘closing’ Army boots whose case had recently been brought to the notice of the House, whose wages were six shillings a week, this meant that one-twelfth of their wages was taken as a contribution towards the expenses of the State, or the equivalent of an income-tax of 18 pence in the pound.’

The example of the army boot makers is important. There had been strikes in Northampton over Army Boot contracts which had broken a previous wage agreement. The contracts meant a cut in the wages of the workers. In the case of the women employed to ‘close’ boots the amount they got per dozen dropped from the agreed two shillings sixpence to one shilling. Their wages therefore fell from 15 shillings a week to six shillings, a large proportion of which was liable to be taxed to pay off the country’s war debt.

That is, ya spent, £31,000,000 for blawin’ brains oot and only £8,000,000 for pittin’ brains in.Joseph Walton

Another Liberal, Joseph Walton wanted more money spent on education and less on the military. Education spending had increased by £6,000,000 while spending on the Army and Navy had grown from £35,500,000 to £71,250,000, he said.

This reminded him of an incident at a Scotch election, where the candidate was heckled by being asked, ‘Am I to understand, Sorr, that whilst you are prepared to spend £31,000,000 over the Army and Navy, you are only willin’ to spend £8,000,000 on education—that is, £31,000,000 for blawin’ brains oot and only £8,000,000 for pittin’ brains in.’

Walton then argued that Britain was spending more on defence than their European counterparts, even in peace time: ‘It was a remarkable fact that while the expenditure on the British Army had gone up during the last fifteen years no less than £16,000,000 sterling, on the other hand the expenditure of the armies of France and Germany combined had diminished £5,500,000 during the same period.’

Taxing a Cuppa

Two weeks later, Francis Channing again entered the debate, this time to argue that the sugar tax should be abolished. This was a vestige of war taxation that had remained in place since the Boer War ended in 1902, and which, as a commodity tax, affected poorer tax payers disproportionately. When the sugar tax was introduced it was estimated the Boer War had cost £148,000,000, and £127,000,000 would be borrowed to meet its costs. Despite the enormous debt built up during the Boer War, the government continued to spend on the military regardless.

The sugar tax was not the only war tax taken through into peace time because of the war debt; others included tea, tobacco, beer and spirits. Such taxes on consumer goods like tea and sugar hit the poor hardest. Channing lost the vote to scrap the sugar tax after Austen Chamberlain, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, defended its continuation.

In 1909, introducing a new budget, David Lloyd George said: ‘This is a war budget. It is for raising money to wage implacable warfare against poverty and squalidness.’

Only six years later, he would be heading the Ministry of Munitions, aiming to ensure the supply of armaments for a different kind of war. However, the resounding success of the Liberals in the 1906 election meant spending was governed by social, rather than military priorities for a brief period. After the war the social vs. military spending debate would be renewed once more.

Military spending now comprises six percent of government expenditure. This is a much lower proportion than before the First World War because of increases in other government spending such as health, education, and welfare. The UK still has the sixth highest military spending globally and the Ministry of Defence has faced much smaller cuts than many government departments since 2010.

When the UK Government claims that there is not enough money to continue to pay for public services such as health, welfare, and education, it is worth considering the military expenditure that they are willing to pay for. The government has little problem paying for such things as fighter jets, aircraft carriers and nuclear weapons.

Alternatives to military spending

The government spends 30 times more on weapons research than tackling climate change. Because arms jobs are paid for by taxpayers, resources can be redirected, and by shifting their priorities from defence spending to combatting climate change, the government could have a dramatic impact. They could secure green jobs for the future and improve, rather than threaten, human security.

Every year £700 million of public money is spent supporting arms exports, often to countries in conflict and regimes that abuse human rights. This subsidy is handed to an industry that accounts for fewer than 55,000 jobs.