About eleven million people voted, which was 38 percent of the population, more than the 34.19 percent who voted in the 2014 local election. This was a huge achievement for a private ballot, organised in just a few months without the resources of a government.

The results were conclusive; across Britain, whether in Scotland, England or Wales, and of whatever social class, the public were in favour of controls on armaments by a majority of over 90 percent.

War was still fresh in the memories of most people in Britain when the ballot took place. Most people would have lost someone they knew in the First World War, and disabled veterans were a visible reminder of how physically and mentally traumatic war could be.

As the next world war threatened, many worked tirelessly to prevent it. All of this helps explain why the Peace Ballot produced such a clear and overwhelming result.

Lord Robert Cecil photographed 5 September 1919 / From the Harris & Erwing Collection at the Library of Congress.

Lord Robert Cecil photographed 5 September 1919 / From the Harris & Erwing Collection at the Library of Congress.

The League of Nations Union

The League of Nations Union was a British organisation set up to educate the public and support the work of the League of Nations, the forerunner to the United Nations. It was an enormous organisation with almost 500,000 members.

The LNU was a politically moderate and respectable organisation that did not always see eye to eye with more radical pacifist groups like the No More War Movement. Unlike pacifists, the League of Nations Union did not advocate complete disarmament. Cecil and Noel-Baker, for instance, believed that there should be an international air force controlled by the League of Nations to keep peace, an idea pacifists (who opposed the use of force of any kind) strongly disagreed with.

The ballot had been tried out on a smaller scale in Ilford, Essex. Although this had been a success, the LNU’s executive committee quailed at the amount of work involved in a national ballot. Couldn’t they do a few more pilots first?

Cecil won out, and the League set about organising the ballot through their local branches and appealing for funds. By August 1934, 34 other organisations had been persuaded to join in. These ranged from the Communist Party to the Association of Headmistresses. Some pacifist groups abstained.

Half a million people, the majority of them women, trod the doorsteps for six months, come rain or shine. They doggedly went back to houses, usually more than once, to collect as many ballot papers as they could. Over 14 million leaflets and other documents were printed for distribution during the Peace Ballot.

The voting rate varied in different areas of the country, and in different constituencies, but the total vote was usually at least 50 percent of the electorate, and in Wales (where women’s peace activism was especially strong), over 60 percent voted.

| Peace Ballot questions | Response to the ballot questions |

|---|---|

| Should Britain remain as a member of the League of Nations? | Yes (97%) |

| Are you in favour of the all-round reduction of arms by international agreement? | Yes (92%) |

| Are you in favour of the all-round abolition of national military and naval aircraft by international agreement? | Yes (82.5%) |

| Should the manufacture and sale of armaments for private profit be prohibited by international agreement? | Yes (90.1%) |

| Do you consider that, if a nation insists on attacking another, the other nations should combine to compel it to stop by (a) economic and non-military measures? | Yes (86.8%) |

| (b) if necessary, military measures ? | Yes (58.7%) |

The results above show how overwhelmingly popular the ideas of the League of Nations and disarmament were at the time. Strikingly, even areas where arms firms employed many local people – Sheffield, Barrow-in-Furness , Coventry, Portsmouth, Birmingham – voted in favour of abolishing the private trade in armaments.

This was not a pacifist vote. The fifth question shows that the public were in favour of implementing sanctions should one nation attack another, while a smaller majority agreed with using military measures if necessary.

If those who normally represent us…are not prepared to face the issue, they are morally bound to get out.A Leeds headmaster

The Peace Ballot results threw down the gauntlet to the government to do something about disarmament and the private manufacture of arms. The official report of the ballot argues: ‘Obviously, the thing to do was to ask John Smith and Mary Brown. It was so obvious, so audaciously simple, that nobody had ever thought of doing it … If our democracy is a true democracy … the sum of their opinions, are … the rock on which the fabric of our government is based’.

A Leeds headmaster wrote to his local MP to say how, standing before an assembly of 450 boys who were likely to fight in the next war, he had become furious about the ballot being ignored by Parliament. He said: ‘We live in an age of democracy, and if those who normally represent us…are not prepared to face the issue, they are morally bound to get out.’

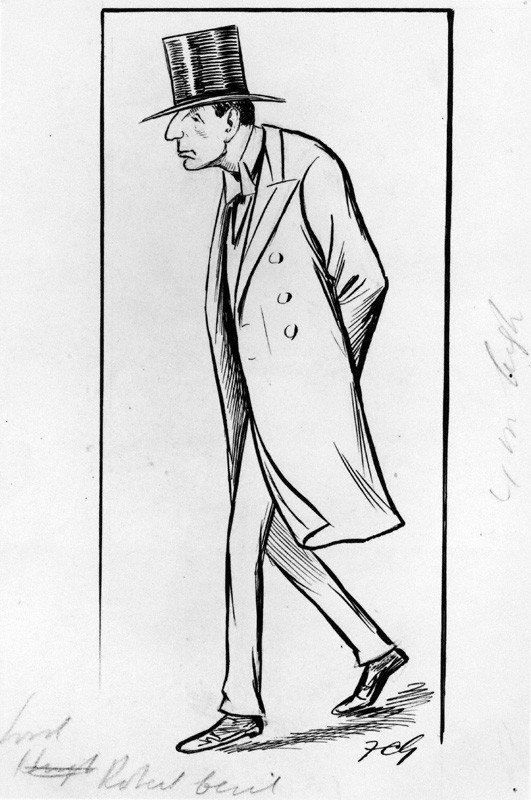

Caricature of 1st Viscount Cecil of Chelwood by Sir Francis Carruthers Gould ('F.C.G.') /© National Portrait Gallery. Creative Commons Licence. http://tinyurl.com/39k5wm

Caricature of 1st Viscount Cecil of Chelwood by Sir Francis Carruthers Gould ('F.C.G.') /© National Portrait Gallery. Creative Commons Licence. http://tinyurl.com/39k5wmThe Conservative Party was generally unsupportive of disarmament and limiting the private manufacture of arms, but at the same time it needed to appease public opinion which clearly desired both of these things.

The Labour Party was little better. Just before the Peace Ballot commenced, Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald told Cecil he thought gestures such as their campaign were ineffective, saying: ‘International opinion is not influenced by them and governments resent them.’

The government may not have liked the Peace Ballot but its results forced them to recognise the strength of feeling in support of disarmament. The Peace Ballot probably contributed to the Royal Commission for the Private Manufacture of and Trading in Arms being established to consider banning the private arms sector.

The ballot was an impressive feat of voluntary activity but is little remembered today, perhaps because as the results were announced the next war was already on the horizon.

Public opinion is against the arms trade now

Today there is significant public opposition to the export of arms to repressive regimes. Opinion polling of the UK public shows that the majority of people oppose selling weapons to human rights abusing regimes. 76% of people said British companies selling military arms and hardware to Libya was the wrong thing to do.

As part of Arming All Sides a group of year 10 George Mitchell School students took to the streets of Covent Garden to ask the public to take part in a modern day Peace Ballot. See a film of the 2014 Peace Ballot, made by RANRED films below.

The results showed a clear majority opposed the arms trade:

– 78% of the people asked thought the arms trade was not a good thing

– 75% thought Britain should not sell arms abroad

– 43% would spend £1 million of government money on education while 34% would spend it on health while only 3% would spend £1 million on the military.

– 46% thought the arms trade should be banned while another 29% were undecided.

– 75% disagreed with museums taking money from the arms trade.

Contact Campaign Against Arms Trade if you are a teacher who’d like to organise a similar activity for your students, or if you’d like to hold a Peace Ballot in your area.